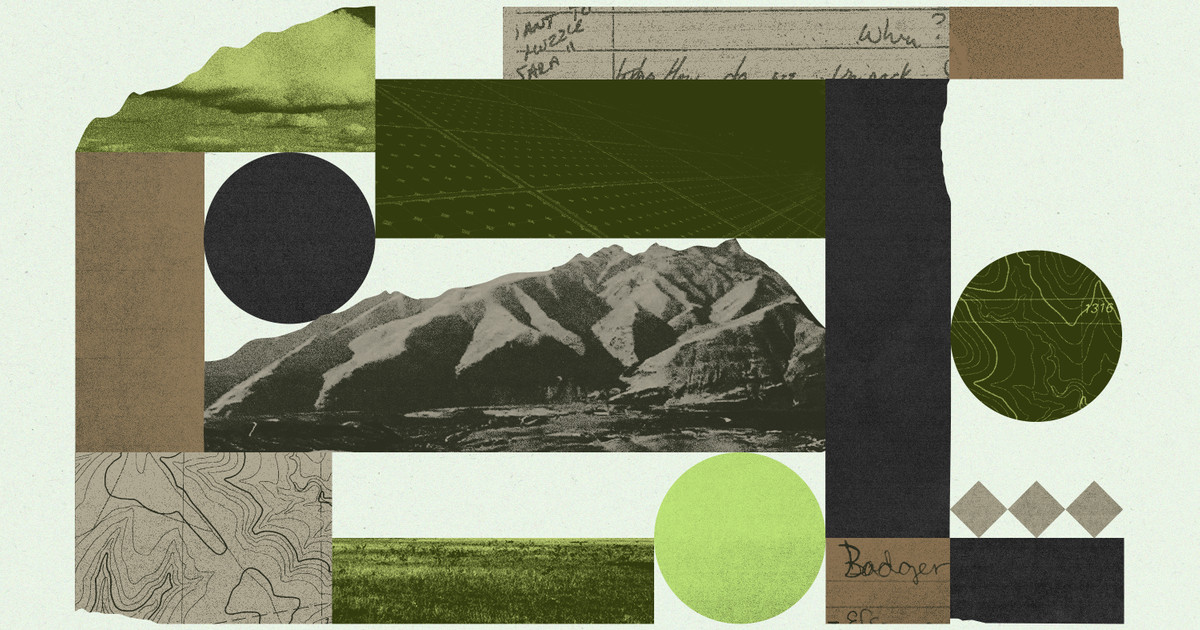

In the autumn of 2021, an 800-page report crossed the desk of Washington state lands archaeologist Sara Palmer. It came from an energy developer called Avangrid Renewables, which was proposing to build a solar facility partly on a parcel of public land managed by the state. Palmer was in charge of reviewing reports like these, which are based on land surveys intended to identify archaeologically and culturally significant resources.

Developers have proposed dozens of similar solar and wind projects across the state — a “green rush” of sorts amid rising fears of climate change. With the projects came more reports.

Often, Palmer, who worked for the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, read the reports and signed off; sometimes she shared notes on any concerns or told the developer to have the archaeologists they’d contracted with do additional fieldwork. This time, as she looked at the report, she grew concerned. The consulting company that Avangrid had hired, Tetra Tech, had included a lot of boilerplate language about human history on the Columbia Plateau, but fewer details than Palmer expected about what was actually found on the land.

Palmer knew that the parcel, located on a ridge called Badger Mountain, near the confluence of the Wenatchee and Columbia rivers, was historically a high-traffic corridor for the škwáxčənəxʷ and šnp̍əšqʷáw̉šəxʷ peoples (also known as the Moses Columbia and Wenatchi tribes). The area would likely be rich in cultural resources, including historic stone structures and first foods, the ingredients that make up traditional Indigenous diets.

Palmer was used to helping developers improve their technical reports to meet state standards. So, as soon as the snow melted, she drove out to Badger Mountain to look at the land herself.

As she walked the sagebrush overlook, Palmer quickly found signs of current-day Indigenous ceremonial activity, as well as ancient sites such as stone structures that can look like natural formations to the untrained eye but serve a variety of functions, including hunting and storage.

Most of the proposed development is on private lands, which Palmer lacked the authority to access. But in about 20 hours of fieldwork on the state-owned parcel, over the course of several days, Palmer said she found at least 17 sites of probable archaeological or cultural importance not listed in Tetra Tech’s survey. She would find more on subsequent visits.

Over the next year, Palmer’s findings — and how she shared them — would pit her against corporate and political forces that seemed determined to push the project through.