For the shellfish industry, high fecal counts detected in areas where shellfish such as oysters are harvested can mean long — and costly — closures.

The fecal matter is associated with human-borne viruses, like norovirus, but the tests that are typically used to measure the fecal matter don’t distinguish between different types of animals, including humans.

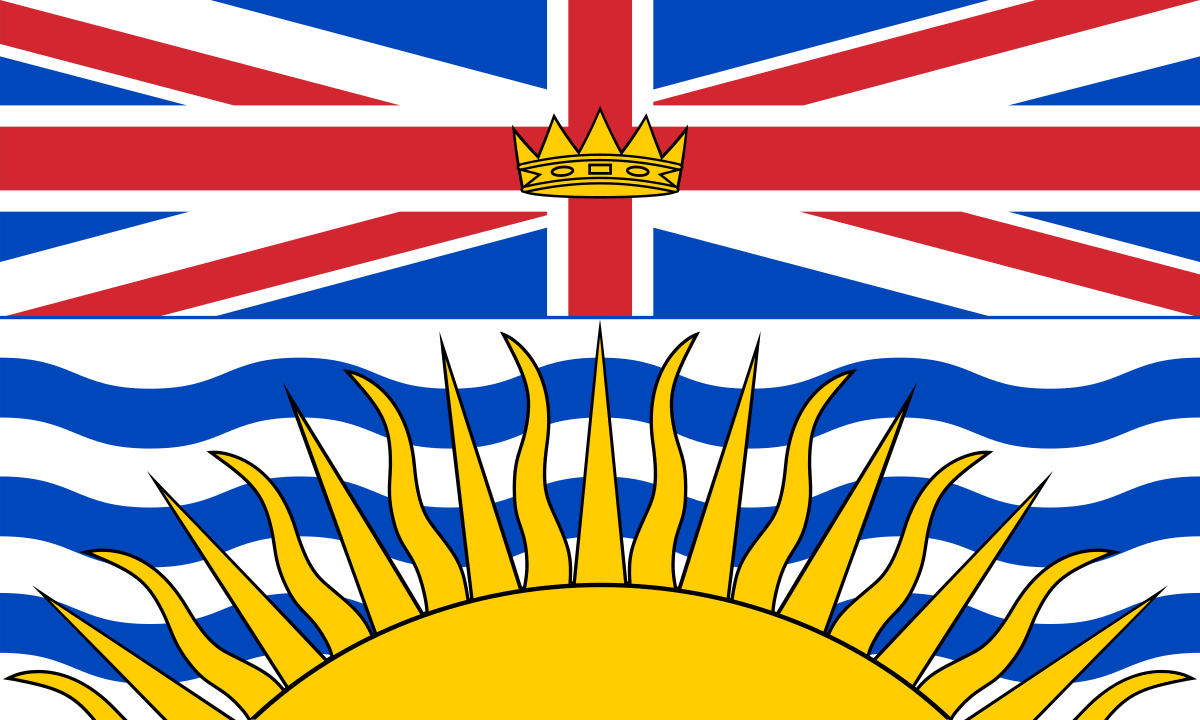

That’s where a new two-year program from Genome B.C. comes in. Researchers have begun using molecular testing to determine, broadly, what sort of animal poop is polluting water, with the goal of making it easier to manage the problem, and hopefully reduce long harvesting closures.

You must log in or register to comment.