- cross-posted to:

- workingclasscalendar

stahmaxffcqankienulh.supabase.co

- cross-posted to:

- workingclasscalendar

Watts Riots (1965)

Wed Aug 11, 1965

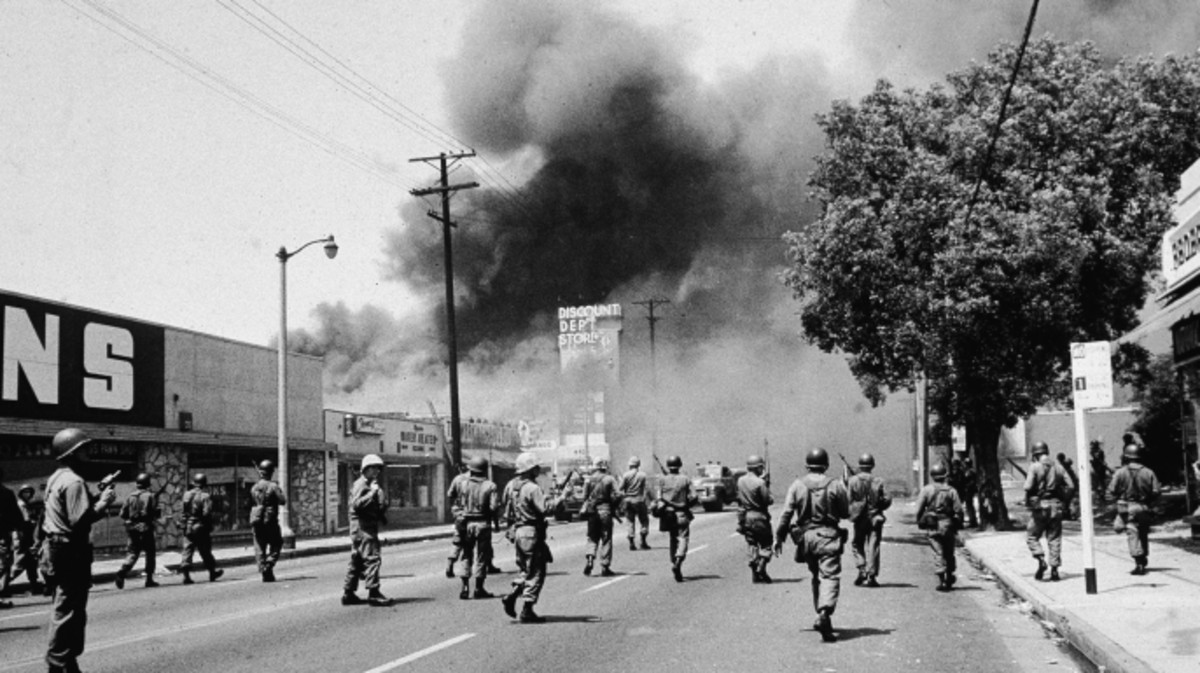

Image: Armed National Guardsmen march toward smoke on the horizon during the street fires in Los Angeles, California, 1965. (Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

On this day in 1965, the Watts Riots began in Los Angeles after police beat Marquette Fry and his family after he was pulled over for drunk driving. The uprising was the largest in city history until the Rodney King riots of 1992, with 34 deaths and $40 million in property damage across a 46 square mile (119 square km) stretch of L.A.

The uprising took place in the context of a highly racialized city, with severely discriminatory housing, educational, and economic practices. The community of Watts was predominantly black and regularly suffered brutality at the hands of police.

After Marquette, along with his brother and mother, were beaten and arrested by police, an angry mob formed and riots broke out. For the next six days, rioters clashed with police and armed National Guardsmen, who had been sent by the thousands to suppress the uprising.

Los Angeles Chief of Police William Parker (incidentally, Parker also coined the phrase “thin blue line” around this time) compared the rioters to the Viet Cong, promising a “paramilitary” response to the disorder. One officer later stated “The streets of Watts resembled an all-out war zone in some far-off foreign country, it bore no resemblance to the United States of America.”

Between 31,000 and 35,000 people participated in the riots, while 70,000 people were “sympathetic, but not active” according to John H. Barnhill. Over the six days of rioting, there were 34 deaths (23 of which were the result of police shootings), 1,032 injuries, 3,438 arrests, and over $40 million in property damage.

Following the uprising’s suppression, a wave of white flight occurred in surrounding areas, leading to significant demographic changes in areas such as Compton and Huntington Park.

A government committee known as the McCone Commission concluded that the cause of the riots was primarily socio-economic, and recommended reforms along these lines. Most of these recommendations were not adopted.

“The whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own masochism and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.”

- Bayard Rustin

- Date: 1965-08-11

- Learn More: www.blackpast.org, en.wikipedia.org.

- Tags: #Riots.

- Source: www.apeoplescalendar.org