Something happened in Luxembourg on Friday that will either bring an end to football’s transfer system as we know it, make the stars even richer, jeopardise player development and ruin hundreds of clubs across Europe, or it will make FIFA rewrite a couple of sentences in its rulebook.

As Sliding Doors moments go, that’s a stark choice: jump on board and take a trip to oblivion, or get the next train to where you went yesterday and every day for the last 20 years.

The agent of change in this analogy is the European Court of Justice ruling (ECJ) that some of FIFA’s Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players — the set of rules that have defined the transfer system since 2001 — are against European Union (EU) law.

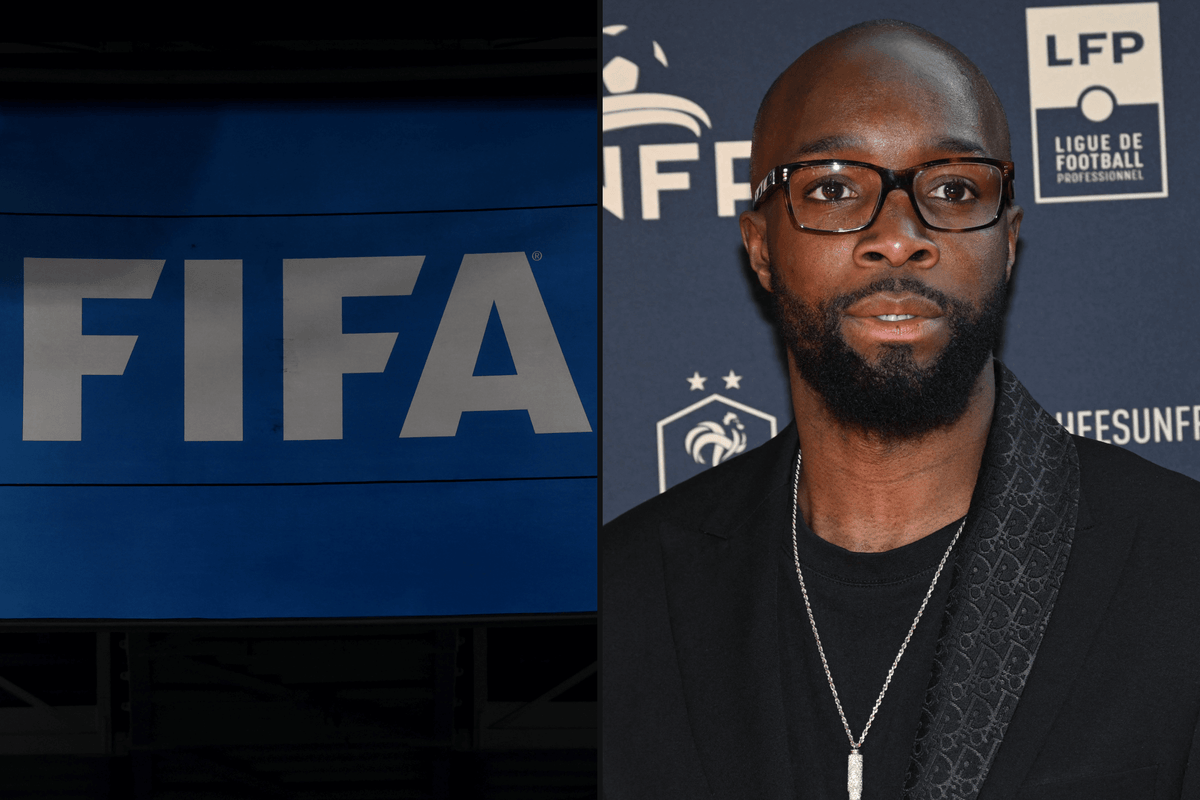

The EU’s highest court was asked to look at the regulations by an appeal court in Belgium that has been trying to settle a row between former player Lassana Diarra, in one corner, and FIFA and the Belgian football federation in the other.

That dispute has dragged on since 2015, but the Belgian court can now apply the ECJ’s guidance to the matter, which should result in some long-awaited compensation for Diarra and a redrafting of at least one article of FIFA’s rules.

But is that it? FIFA thinks so but The Athletic has heard from many others who say, no, that train has left the station and nobody knows where it is going.

So, let’s dive through the closing doors and see where we get to. But, before we do, let’s make sure everyone knows where we started.

What on earth are we talking about?

Good starting point.

After stints with Chelsea, Arsenal, Portsmouth and Real Madrid, Diarra moved to big-spending Anzhi Makhachkala in 2012. His time in Dagestan ended abruptly when the club ran out of money a year later but he had played well in the Russian league and Lokomotiv Moscow signed him to a four-year deal.

Sadly, after a bright start, the France midfielder fell out with his manager, who dropped him and demanded Diarra take a pay cut. The player declined and the situation deteriorated. By the summer of 2014, he had been sacked for breach of contract and Lokomotiv pursued him via FIFA’s Dispute Resolution Chamber for damages.

Using a rule of thumb developed over the previous decade, FIFA decided Diarra owed his former employer €10.5million (£8.8m, $11.5m) and banned him for 15 months for breaking his contract “without just cause”, its catch-all phrase for messy divorces. Diarra appealed against the verdict but it was confirmed in 2016 by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), albeit with a slightly reduced financial hit.

In the meantime, Diarra was offered a job by Belgian side Charleroi in 2015. They got cold feet when they realised that article 17 of FIFA’s transfer regulations — “the consequence of terminating a contract without just cause” — made them “jointly and severally liable” for any compensation owed to Lokomotiv and at risk of sporting sanctions, namely a transfer embargo.

Stuck on the sidelines, Diarra decided to sue FIFA and its local representative, the Belgian FA, for €6million in lost earnings.

Once his ban had expired in 2016, his football career resumed with a move to Marseille, and he would eventually retire in 2019 after stints with Al Jazira in Abu Dhabi and Paris Saint-Germain. His row with the football authorities continued, though, and, with the support of the French players’ union and FIFPRO, the global players’ union, he took it all the way to Luxembourg City, where he won, on Friday morning.

All caught up?

Erm… no — what has he won?

Ah, well, it depends on who you believe.

According to his lawyers, Jean-Louis Dupont and Martin Hissel, Diarra has won “a total victory”, but not just for him.

“All professional players have been affected by these illegal rules (in force since 2001!) and can therefore now seek compensation for their losses,” they said.

“We are convinced that this ‘price to pay’ for violating EU law will — at last — force FIFA to submit to the EU rule of law and speed up the modernisation of governance.”

As a heads-up, Dupont has considerable experience in this area — and we will return to him shortly.

FIFPRO, unsurprisingly, agrees. In a statement issued immediately after the decision was published, the union described it as a “major ruling on the regulation of the labour market in football (and, more generally, in sport) which will change the landscape of professional football”.

Later on Friday, it published a longer statement that expanded on its belief that this was both a big W for Diarra personally but also a class action victory for all players.

“It is clear the ECJ has ruled unequivocally that central parts of the FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players are incompatible with European Union law,” it said.

“In particular, the ECJ has stated that the calculation of compensation to be paid by a player who terminates a contract ‘without just cause’ — and the liability for the player’s new club to be jointly liable for such compensation — cannot be justified.”

It continued by saying these clauses of article 17 of the regulations “are the foundation of the current transfer system and have discouraged numerous players from terminating their contract unilaterally and pursuing new employment”. Furthermore, it said, the ECJ agreed with the union that players’ careers can be short and “this abusive system” can make them shorter.

It leapt on the more memorable sections of what is a bone-dry, 43-page judgment (currently only available in French and Polish), by pointing out that the court’s judges think the criteria FIFA used for calculating Diarra’s fine, and other sanctions in cases like his, are “sometimes imprecise or discretionary, sometimes lacking any objective link with the employment relationship in question and sometimes disproportionate”.

It then suggested that the only way to remedy this, and the other problems the court highlighted, is for FIFA to talk it through properly with the unions and their members.

“We commend Lassana Diarra for pursuing this challenge which has been so demanding,” it continues.

“FIFPRO is proud to have been able to support him. Lassana Diarra — like Jean-Marc Bosman before him — has ensured that thousands of players worldwide will profit from a new system…”

Hold on… Bosman?

Yes, Bosman, another midfielder who did not quite live up to his early promise as a player but confounded all expectations as a labour-rights revolutionary and begetter of new worlds.

In case you are hazy on the details, Bosman found himself in a similar spot to Diarra in 1990 when he was out of favour at RFC Liege. The difference, however, is that he was out of contract and simply wanted to take up a new one just over the French border in Dunkerque. Liege said words to the effect of “OK, but only if they pay us half a million”, as was the custom back then.

Five years later, Bosman was finished as a player but not before he had claimed football’s most famous ECJ ruling — one that meant players were free agents once their contracts had expired, massively increasing their attractiveness to new employers, and bringing down European football’s long-standing restrictions on the number of foreign players clubs could field.

Dupont was his lawyer and that is partly why agents, union officials and some legal experts have been previewing Diarra as “the next Bosman” ever since one of the ECJ’s advocate generals — senior lawyers who help the judges make their decisions — published his non-binding opinion on the case earlier this year. The judges do not have to follow that guidance, but this time they did, almost verbatim.

So, that is why my phone started buzzing with contrasting predictions of what Diarra’s win would mean for the game long before anyone had got past the preamble of the ruling.

OK, what might happen next, then?

To answer this, it is perhaps useful to go back to Bosman. When that bombshell ruling was delivered, clubs said the world would end, as the players now had all the power, which meant there was no point having academies, as the brightest talents would leave for nothing, and fans could forget getting attached to anyone, as the best players would swap teams every year.

The verdict came too late to help Bosman. But when the likes of Sol Campbell and Steve McManaman ran down their contracts at Tottenham and Liverpool respectively, in order to secure moves to new clubs, on much higher wages, it looked like the doom-mongers were onto something.

But six years after Bosman, the clubs, aided by FIFA and European football’s governing body UEFA, managed to persuade the European Commission that too much freedom of movement was bad for football and what that industry really needed was contractual “stability”.

The result was the first iteration of FIFA’s Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (RSTP). The authorities called it a compromise between the clubs’ need to retain some control of their most valuable assets and every other EU citizen’s right to quit one job and take another, anywhere in the single market. The unions called it “an ambush”.

In 2006, however, the pendulum swung towards the players again when a Scottish defender called Andy Webster decided to use a provision in the rules — the right for a player to buy out their contract after a prescribed protected period — to force a move from Hearts to Wigan.

As he was over 28, his protected period was three years and he was in the final year of a five-year deal, so he was OK to move. Unfortunately, nobody had settled on a formula for deciding how much he should pay his old club.

Hearts reckoned Webster, an international, was worth £5million but his lawyers offered them £250,000, a sum equal to what he was owed in wages for the last year of his deal.

Like Diarra, they took it to FIFA’s Dispute Resolution Chamber (DRC), which decided Hearts were owed £625,000, a sum based on his future earnings and the club’s legal costs. He appealed against that verdict at CAS and it reduced the compensation by £150,000 but backed the gist of the ruling.

For a year, it looked like Webster had become “the new Bosman” but, in 2007, the pendulum swung back towards “stability” when Brazilian midfielder Matuzalem tried to engineer “a Webster” out of Shakhtar Donetsk to Real Zaragoza.

After the usual visits to the DRC and CAS, football had a new, more club-friendly precedent for deciding the compensation jilted parties were owed by these unilateral contract-breakers, a sum based on the player’s remaining wages and his unamortised transfer fee.

Confused? Don’t worry, it was a bigger number and therefore a larger deterrent.

So, the pendulum is about to swing again?

Again, it depends on who you ask.

For FIFA, this is a great big nothingburger.

Its immediate response to the news from the ECJ was to jump on the sentences in the ruling that supported its right to have rules that breach EU rules on freedom of movement and competition because professional sport is not like journalism, law and other humdrum jobs. It has “specificity” and should therefore be exempted from certain principles, providing they are for a “legitimate objective”, such as “ensuring the regularity of interclub football competitions”.

Therefore, FIFA noted, the court still agrees football can justify rules aimed “at maintaining a certain degree of stability in the player rosters of professional football clubs”.

Phew, that should save most of the rulebook, then, right?

“The ruling only puts in question two paragraphs of two articles of the FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players, which the national court is now invited to consider,” a FIFA spokesperson said, referring specifically to two of Diarra’s main objections: the joint liability of the new club in a dispute like his, and the withholding of the International Transfer Certificate, which players need for a cross-border deal, until compensation has been paid.

FIFA’s chief legal and compliance officer Emilio Garcia Silvero doubled down on this “Am I bothered?” take with a later statement that said: “Today’s decision does not change the core principles of the transfer system at all.”

And he might be right. After all, it is now up to the Belgian court to apply the ECJ ruling to the Diarra case, which could clarify things slightly and certainly provide some time for the dust to settle.

It is also possible to read the ECJ ruling and imagine a scenario in which FIFA places all liability for breaching contracts “without just cause” on the player but puts in place a less onerous and more transparent formula for working out how much compensation should be paid.

And if FIFA wanted to increase its chances of gaining union support, it could also broaden the list of reasons why a player might have cause to break a contract. At present, it thinks the only justifications for a player to breach are not getting paid for months on end or the outbreak of war.

But there are plenty of people who have now read the ruling and do not believe FIFA is going to get away with a few tweaks.

As mentioned, FIFPRO and its member players’ associations are convinced the entire transfer regime is up for grabs and FIFA will now have to enter into the types of collective bargaining agreements that are central to professional sport in North America.

As David Terrier, the president of FIFPRO Europe, puts it: “The regulation of a labour market is either through national laws or collective agreements between social partners.”

Ian Giles, head of antitrust and competition for Europe, Middle East and Africa at global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright, is on the same page as the unions when it comes to the potential ramifications of the ruling.

“The decision essentially says the current system is too restrictive and so will have to change,” he explained.

“In terms of free movement, the ECJ recognises there may be a justification on public interest grounds to maintain the stability of playing squads, but considers the current rules go beyond what is necessary.

“It’s a similar story regarding the competition law rules. The ECJ has deemed the relevant transfer rules to amount to a ‘by object’ restriction — a serious restriction similar to a ‘no-poach’ agreement. Concerns about labour market restrictions, including ‘no-poach’ agreements, are a particular area of focus for competition authorities globally.

“Under competition law, it’s possible for otherwise restrictive agreements to be exempt — and therefore not problematic — if they lead to certain overriding benefits, but it’s generally difficult for ‘by object’ restrictions to meet the specific requirements for exemption.”

Giles’ point about the ECJ saying article 17 of the regulations is a “by object” restriction has been noted by other experts, as it means the court is effectively saying it is a restriction, end of story, and there can be no justification for it, no matter how noble the objective.

In terms of what this might mean for the industry, Giles can only speculate like the rest of us.

“It’s entirely possible this means players will feel they can now break contracts and sign on with new clubs, without the selling club being able to hold them or demand significant transfer fees,” he said.

“This will likely result in reduced transfer fees and more economic power for players, but over time things will have to stabilise to allow clubs to remain economically viable. Smaller clubs who rely on transfer fees for talent they have developed may well be the losers in this context.

“The key question now for FIFA will be how they how can adapt its transfer rules so that they are less restrictive and therefore compatible with EU law, while seeking to maintain the stability of playing squads. It will also be interesting to see whether more players start to breach their contracts in the meantime, emboldened by the ECJ’s judgment.

“Something else to keep an eye on is whether we could see other players bring damages claims, alleging they’ve suffered harm as a result of FIFA’s transfer rules, with damages claims for breaches of competition law generally on the rise in the UK and Europe.”

Right, has anyone else chipped in?

Yes! Not that they have shed much light on where we are heading, although they have confirmed where loyalties lie.

European Leagues, the organisation that represents the interests of domestic leagues across the continent, took a player-friendly stance by saying the decision confirmed that “FIFA must comply with national laws, European Union laws or national collective bargaining”.

It added that it stood for contractual stability but only when it is “safeguarded by national laws and collective bargaining agreements negotiated and agreed by professional leagues and players’ unions at domestic level”.

The European Club Association (ECA), however, adopted an “if ain’t broke (for us), why fix it” approach.

“Whilst the judgement raises certain concerns, the ECA observes that the provisions analysed by (the court) relate to specific aspects of the FIFA RSTP, with the football player transfer system being built on the back of the entire regulatory framework set out in the (regulations) which, by and large, remains valid,” it said.

“More importantly, the ECJ did recognise the legitimacy of rules aiming at protecting the integrity and stability of competitions and the stability of squads, and rules which aim to support such legitimate objectives, including among others, the existence of registration windows, the principle that compensation is payable by anyone who breaches an employment contract and the imposition of sporting sanctions on parties that breach those contracts.”

As a champion of clubs large and small, the ECA noted that the transfer system “affords medium and smaller-sized clubs the means to continue to compete at high levels of football, especially those who are able to develop and train players successfully”.

Whether that is actually true or not is the subject of a much bigger and long-running debate. But it is certainly an attractive idea and sometimes that can be enough.

What do football’s transfer movers think?

My colleague Dan Sheldon spoke to Rafaela Pimenta, a football agent who represents Erling Haaland, Matthijs de Ligt, Noussair Mazraoui and other top stars. She told The Athletic: “If you talk to agents, they are over-excited because, finally, the players are going to get heard. How many times are we still going to see them crying after having their careers destroyed because they are being denied a transfer?”

She made it clear, though, that the focus now should be on conversations between football’s various stakeholders to define what the new rules should be.

“For players, this can be a landmark and I hope players will use it wisely,” she said. “This is not an excuse for them to do whatever they want; it is a reason to stand up for their rights.

“I think what the challenge here is to make sure their voices are used responsibly. And by that I mean let’s talk and have this discussion, let’s lead the process and understand what clubs need, what players need and what is the compromise.

“If there is no balance and one side, either the players or the clubs have all the power, then it will go wrong again.

“I understand clubs need to have assets, but they need to understand that players are human beings and sometimes things don’t go according to plan and they cannot become the asset that stays there parked on a corner.”

That is probably enough excitement for one day. We shall back with more analysis when the pendulum swings again.