- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

In the 1960s, researchers from France set off 17 nuclear bombs in the Algerian Sahara to test both the technology behind such weapons and their destructiveness.

The site was chosen due to the emptiness of the vast desert region. Unfortunately, the remoteness of the location was not enough to prevent thousands of Algerians from radiation fallout exposure.

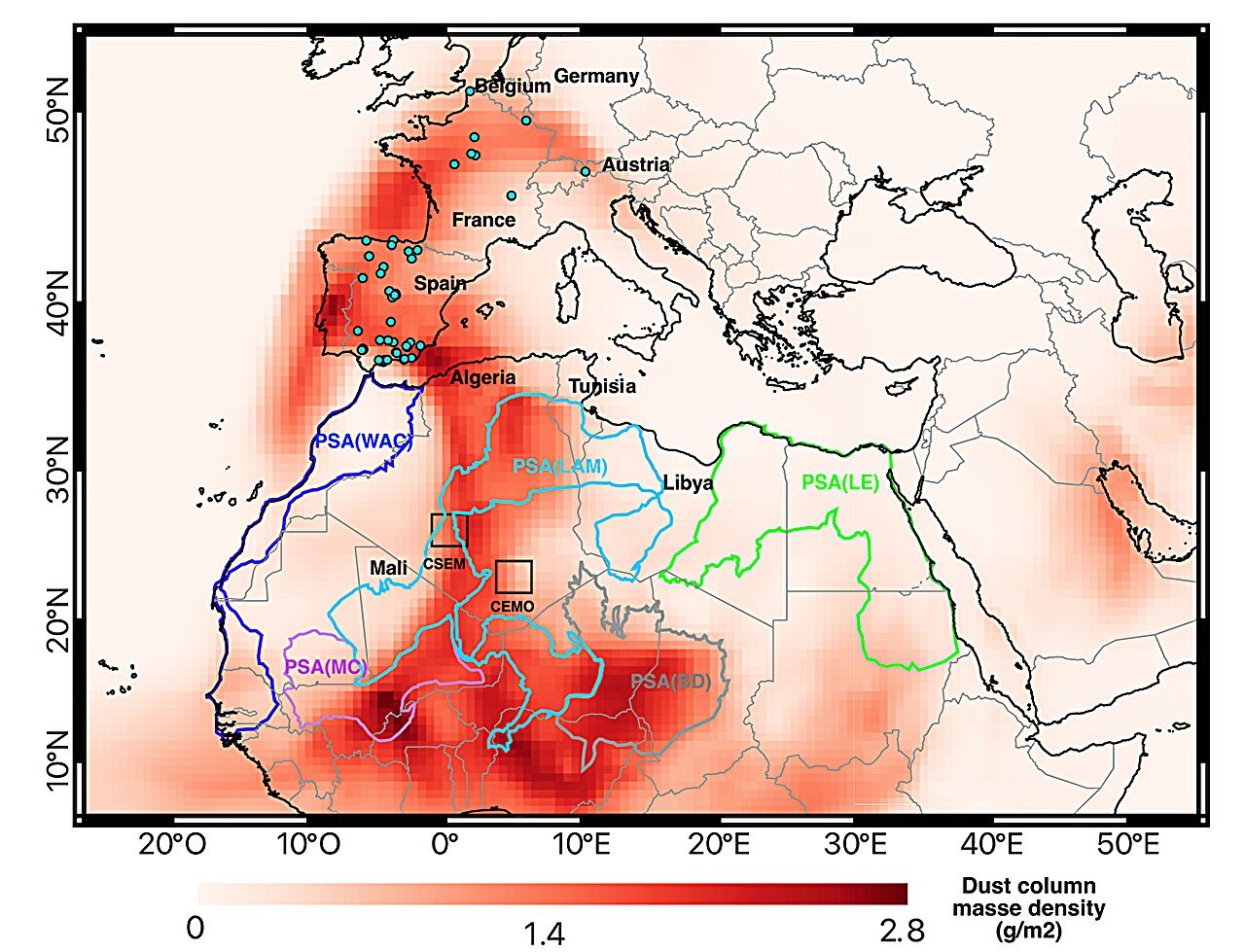

More recently, in 2022, a dust storm developed over the same part of the Saharan desert and carried the dust north, making its way to parts of Europe. In this new effort, the research team wondered if radioisotopes in the dust had been carried along with it, potentially endangering people in Europe. To find out, the researchers selected 53 dust samples from multiple sites in Europe and tested them.

Testing showed that the dust had indeed arrived to the test sites from Algeria’s Reggane region, where the test blasts had occurred. Testing also showed radioactive isotopes in the dust—but not at levels that would cause harm, at least according to European Union’s safety rules. What was surprising, though, were the plutonium ratios, which are unique based on the fuel used to build the bomb.

The researchers found them to be below 0.07, which ruled out the radioactivity coming from a French-made bomb. Instead, the ratios, which averaged 0.187, more closely matched those that were trademarks of bombs exploded by the U.S. and U.S.S.R. back in the 1950s and 60s.

Neither the U.S. nor the U.S.S.R. conducted bomb tests in the Sahara, but both tested bombs elsewhere that were far more powerful than those tested by France in the desert. Such blasts spewed material so far into the atmosphere that it came down thousands of miles away, including in the Algerian desert.