- cross-posted to:

- workingclasscalendar

stahmaxffcqankienulh.supabase.co

- cross-posted to:

- workingclasscalendar

Jourdon Anderson Letter (1865)

Mon Aug 07, 1865

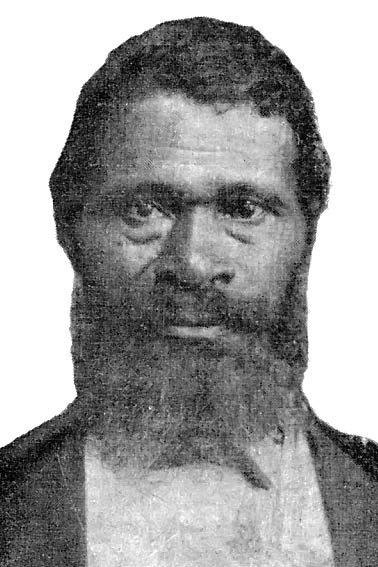

On this day in 1865, freedman Jourdon Anderson (1825 - 1907) wrote a humorous and pointed response to decline the request of his former master to return to the plantation, which had fallen into disrepair after the Civil War.

The letter’s dry wit has been compared to the style of Mark Twain, and it became an immediate sensation, becoming published in the press a few weeks later.

Jourdon had been enslaved since he was a child in Wilson County, Tennessee, working the plantation of the Anderson family. In 1864, Union Army soldiers camped on the Anderson plantation and freed him. Subsequently, he moved to Dayton, Ohio with his family, finding work as a sexton with the Wesleyan Methodist Church.

In 1865, he received a letter from Colonel P.H. Anderson, his former master, who requested that Jourdon return to the plantation in a last-ditch to save the farm, which had fallen into disrepair after the Civil War.

On August 7th, 1865, Jourdon dictated his response. Here are some excerpts (the letter in full is linked below):

"I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house.

…[My wife and I] have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you…I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars.

Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future.

…P.S.—Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me."

Jourdon’s offer was declined, and he continued to live in Dayton, dying there at the age of 81 in 1907. Colonel Anderson, having failed to attract his former slaves back, sold the land for a pittance to try to get out of debt, dying two years later.

Prior to 2006, historian Raymond Winbush tracked down the living relatives of the Colonel Anderson, reporting that they “are still angry at Jordan for not coming back”, knowing that the plantation was in serious disrepair after the war.

- Date: 1865-08-07

- Learn More: www.smithsonianmag.com, en.wikipedia.org.

- Tags: #Labor.

- Source: www.apeoplescalendar.org