Or “II,” if you prefer, since Bradley now seems to express their model numbers in terms of Roman numerals. It takes all kinds, I guess.

On our last foray we took a look at the Kershaw Moonsault which I ultimately put in my Not Recommended pile on the grounds of it having very slick technology, but having crap for feel in the hand despite coming with zooty ball bearing pivots. I said there are better similar balisongs for the money. Which ones?

Well, this one, for a start.

Here’s the Bradley Kimura. This is kind of an OG; Unlike the last pair of knives I’ve looked at, it’s not new. In fact, I’ve had this knife in my collection since 2012. Thus, in the pictures you will see some wear from use and pocket lint. I did give the thing a quick spritz before doing the photography but, as you’ll see, maybe I could have done a better job. Oh well.

This particular model, the Kimura, 2 is not made anymore. But the Kimura series as a whole is, in an array of various handle styles and colors, and near as I can tell the mechanisms are identical. As usual for Balisongs, some of these models don’t stick around on the market for long. And then when they disappear they tend to become collector’s items. I paid $90 for this Kimura 11 years ago, and current ones go for $130 or so. Sometimes you can score one for around a hundred bucks. I guess that’s inflation for you, but really in this kind of market it’s not too awful. (I know I’ve linked to BladeHQ a bunch of times lately, and I promise it’s not because I have any affiliation with them – other than giving them a lot of my money over the decades.)

Superficially the Kimura 2 has one big thing in common with the Moonsault: Both of these are full steel knives, with both the blades and handles made out of metal and no liners, handle scales, or any other materials. The Kimura’s not as comically enormous, though: It’s 5-1/8" closed by my measure and 8-7/8" in length when open. Closed width is 1-1/16", as usual not including the ears on the blade or the distance added by the head of the latch. The blade is 3-7/8" long from handle tips to point, with about 3-1/2" of usable edge. That’s a bit nebulous, because there is no choil and where the cutting edge actually becomes defined enough to be useful is up for debate by a small fraction of an inch. Blade width is 29/32" at its widest point, in the middle of the belly. Blade thickness is 0.121", just under 1/8".

Due to the all steel construction, the Kimura is pretty weighty. 159 grams by my scale, or 5.6 ounces.

Taken all together that means it has a pretty similar design intent to the Moonsault, which is a solid weight in the hand, with heavy handles that provide a lot of inertia. But it’s still noticeably smaller and a little bit lighter, which I think works in its favor.

Here’s a comparison lineup between the Kimura (top), the Kershaw Moonsault (middle), and the venerable Benchmade Model 42 (bottom). In this shot I lined them all up by their latch ends with a ruler, so you can get a feel for the difference in size. (I have to say, I honestly never noticed until this very moment that the Kimura is noticeably shorter than the Model 42. I certainly would have gotten that question wrong on pub trivia night. Yesterday I would have sworn to you that they were the same size.)

So that’s that. And then, just about everything else about it is totally different.

The Kimura is a very traditionally designed knife with a normal dual kicker pin design. The blade is spear pointed with a very pronounced belly, widening in the middle and thinning a bit at the base and especially the tip. This makes it almost a leaf point, if you ask me (although a tanto point variant is also available). It’s single edged, of course, and doesn’t make any pretension whatsoever of having a false edge on the back. Much of it is a flat grind as well, which is very nice. It’s made of 154CM, so not exactly an exotic supersteel, but mine’s held up perfectly well over the years. It has the same nice satin finish on the blade as the handles. Although, the big “Bradley” logo in the middle of it is a little gaudy, in my opinion. The reverse bears the inscription that, yes, this knife is made in the USA. Strangely, the type of steel used is not marked on the knife anywhere. That’ll make it no good for showing off to your friends. You’ll have to impress them with your flip tricks instead, I guess.

Here’s the reverse, only because the two sides are different. One side has these flush fit smooth heads on the pivot pins, while the other side has button headed screws. It’s quite minimalist, very Bauhaus.

You can also see that the kicker pins are very even, very straight, and have nicely machined tops. No swarf, splines, or other ugliness is visible. This is usually a pretty good sign of quality.

The latch has a round fillister head (there’s your word of the day) and is a plain swivel with no squeeze release or spring. It’s very easy to kick open with your pinky when you’re holding the knife, though. Its travel is stopped by the handle spacers and while it has enough free arc to strike the opposite handle, it can’t touch the blade. It also has a pretty close tolerance against the handle scales it’s sandwiched between, which makes it feel pleasingly precise – and also keeps it quiet.

By the way, it looks like there is a screw missing opposite the latch pivot, but there isn’t. The handle scales are mirror images of each other, front left to rear right and front right to rear left. Only having to make two parts instead of four probably reduces machining costs a bit, but that means there is an empty screw hole in two of the scales in the void where the latch head goes.

Between the handles are these groovy diabolo style spacers. One of these also serves as the end stop for the latch so it can’t swing too far.

The Kimura’s feel is excellent. The pivots ride on sintered bronze washers which provide a nice level of glide. The pivot tolerances are also very close and high quality, leading to a knife that spins and flips very freely, aided by those heavy handles, and is pleasingly free of rattle and any kind of noticeable play against the axis.

It’s quiet, too. The latch makes a pleasant click when it strikes the end of its travel, and doesn’t clank or jingle. On rebound against either of the kicker pins, the entire knife makes a solid sounding but not excessively loud single clack. Notably, nothing resonates, buzzes, vibrates, or rings. Each impact event is single and contained, and doesn’t carry on for ages like the Kershaw Moonsault did. It sounds dumb but I think this genuinely makes the knife a little easier to use gracefully since you can feel precisely when you’ve hit a rebound. The feedback is instant and short, never muddled or vague.

It also helps that there isn’t a single hard edge anywhere on the handles. The handle edges are all exquisitely rounded, and all the holes are nicely chamfered. This allows it to roll nicely in your hand and it feels pretty good while you’re doing it. Not the best of the best, but certainly very good.

There’s no pocket clip or any other provision for carrying it, though. The knife doesn’t even come with a pouch. For my purposes, I made a little Kydex belt holster for it. Up to you if you want it bouncing around in your pocket or not, but if I were you I would not put anything else in there with it lest you scratch up that nice satin finish.

Wiggle test! The Kimura scores pretty well, with maybe a hair under 1/8" of play at the ends of the handles, if you push up real good on one and down on the other. That’s really not bad for a knife that doesn’t actually have any fancy bearings.

Ancient Ninja Secret: If you want to get the Kimura apart, the key is to undo the pivot screws while the knife is latched shut. If you don’t, the female end of the pivot pins will just spin in place and obviously there’s no screw head on that side to put a tool into. When it’s latched, they lock in place due to the tension running down the handles. The same trick is required on reassembly.

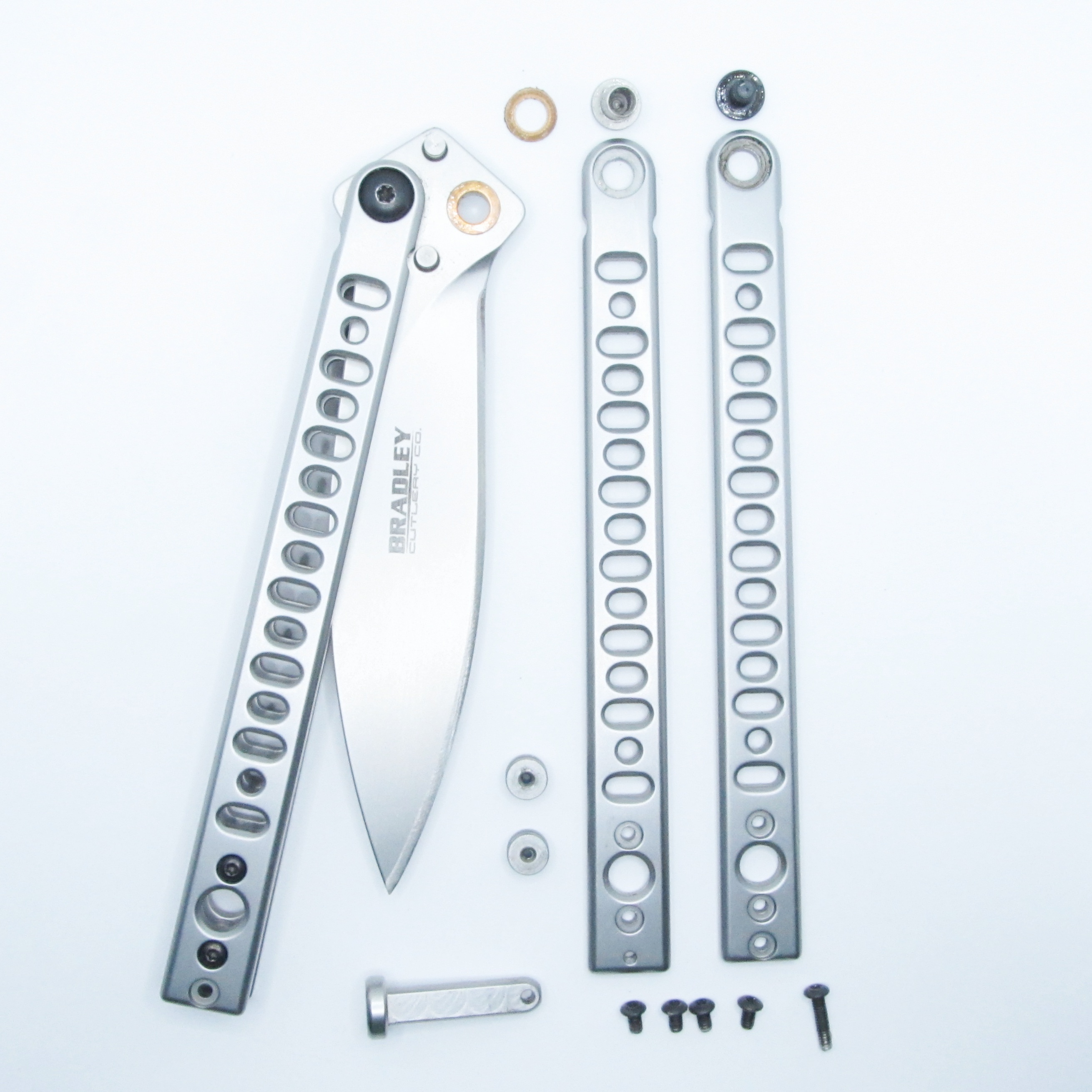

Here’s what the inside of the Kimura looks like, complete with 11 years of accumulated grit, dirt, and pocket fuzz. All four of the spacer screws are identical; the only oddball is the longer screw that goes through the latch. I only did one side since with the exception of the latch they’re the same. I took apart four knives back to back today and I’m running out patience for little tiny Torx screws that want to leap under the furniture and vanish. Sue me.

Here you can see the bronze washers, and also one of the pivots disassembled. The pivots are Chicago screws, threaded only in one end. The bronze washers provide a low level of friction between the blade heel and inner surface of the handles.

I don’t normally get into this sort of thing, because I always thought it was really dumb to say something like “really sharp!” like you read in every single Amazon review of every knife ever. Of course it’s sharp – it’s a knife. If it’s not sharp, it’s not a big deal to make it sharp, and I hope you’re equipped to do so or else you won’t be using your knife very long, will you? I mean, duh.

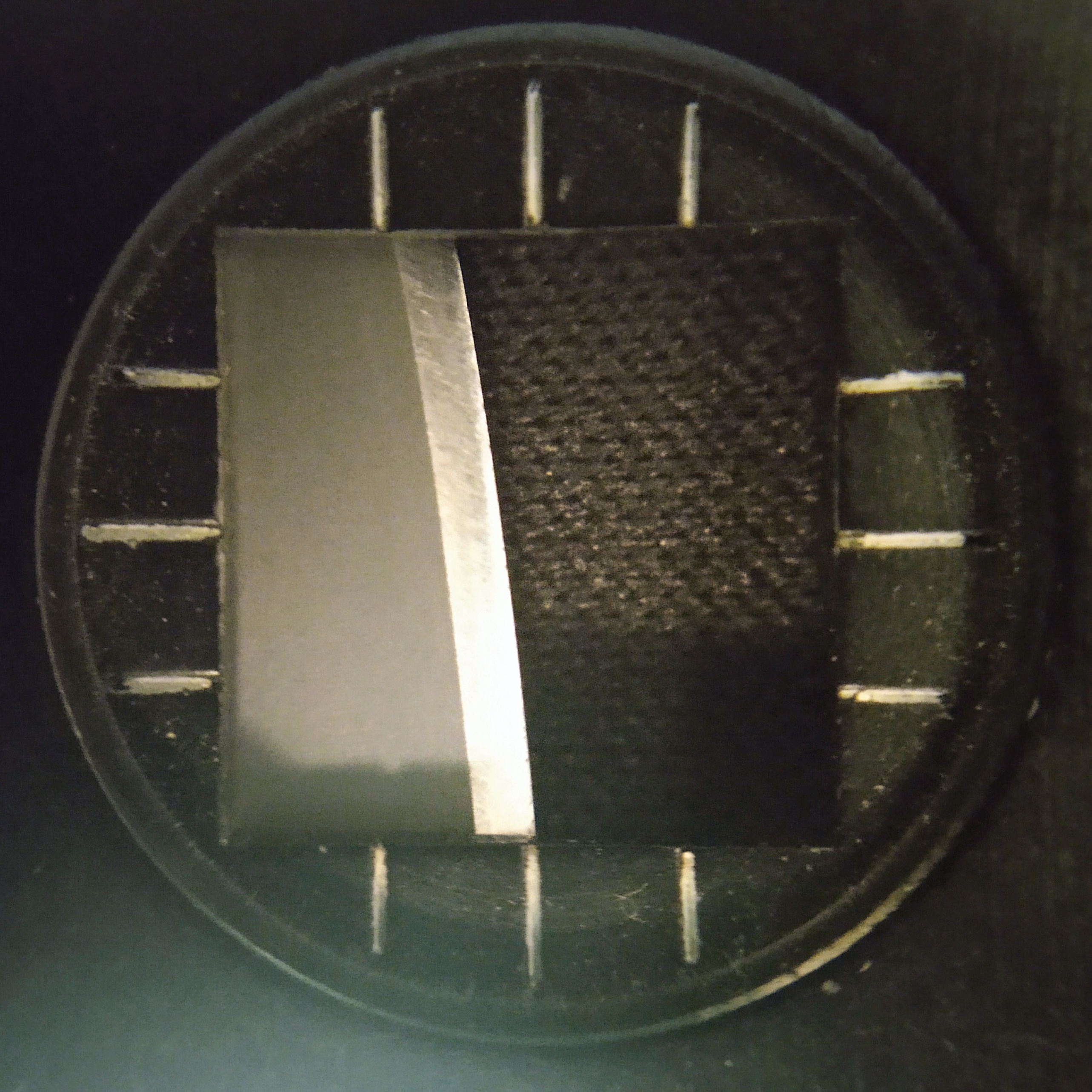

Ahem. Anyway, here’s a loupe shot of my Kimura’s edge. Special mention has to go to this knife, I think, because I found that the edge grind on mine was extremely consistent out of the box, and it took a dressing from my Spyderco Tri-Angle at 30 degrees like it was friggin’ designed for it. The consistency of angle between both sides (or “trueness”) of the edge grind on any given knife is another reasonable indicator of quality, and I found that the Kimura was dead on from the factory, all those years ago. It took a minimum of effort to make this thing stupidly sharp, which is… exactly what you want on a balisong you’ll be flipping around, ready to liberate a fingertip. Right???

The Inevitable Conclusion

Should you buy one? Well, do you want a very solid and very nicely made balisong knife for a non-insane amount of money? If so, the answer is yes. You can’t buy this one, though. You’ll have to pick from the array of new handle styles. But this knife is in my opinion every bit of 85% of a Benchmade Model 42, except a '42 will cost you the thick end of a thousand dollars if you can even get your hands on one at all, but this thing you can have shipped to your door tomorrow for 130 bucks.

As previously stated, the value proposition of most balisong models is not quite the same as regular pocketknives bought by Normal People. Balisongs are a niche product and by and large fairly expensive for a given quantity of knife. If you just want to use the thing for opening your Amazon packages or whittling around the campfire, it’s probably not a very good value nor suited to the task. It is also not an EDC knife. It’s still pretty big compared to most EDC’s, has no clip, and doesn’t come with a holster or pouch. What it’s for is flipping, and playing with, and showing off, and then when you feel like it really showing all those envelopes who’s boss.

If all you’ve got is a $20 cast potmetal piece of shit from the farmer’s market the Kimura will be a revelation by comparison. If you have a $900 exotic semicustom limited production run collector’s flipper, well, you might just handle this and wonder what it was you paid for.

Hmm. Three balisongs in three days, and tomorrow’s Wednesday. Am I scheming something?

/closes eyes and crosses fingers/ “tatersong, please let it be the tatersong”