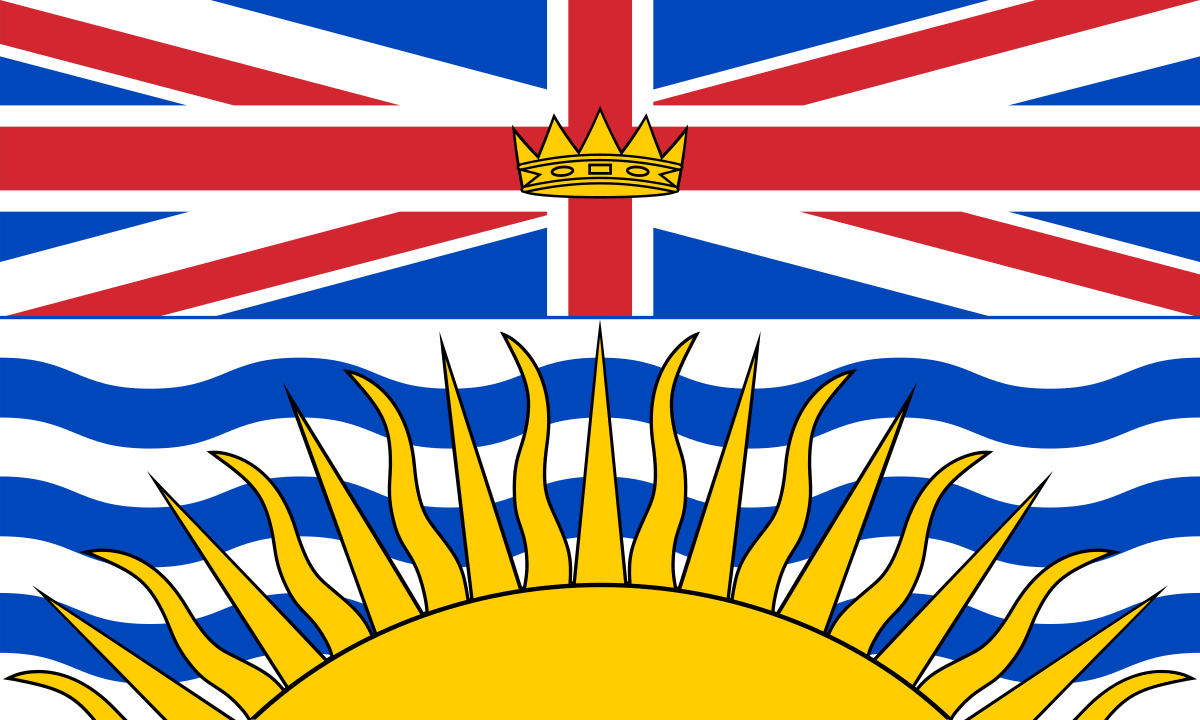

As I write this, I’m getting ready to leave for my seventh season of tree planting. I’ve had an eye on the weather all winter, watching as the snowpack levels in British Columbia reach lows not recorded since at least 1970, watching as rivers — like the confluence of the Nechako and Fraser rivers in Prince George — run dry.

According to data from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s National Agroclimate Information Service, by the end of March this year 85 per cent of B.C. was considered abnormally dry or in moderate to exceptional drought. The region that I’ll be planting in, near Burns Lake, is one of the driest in the province.

Over the years I’ve had many doubts about the ecological benefits of the province’s reforestation practices.

But last season marked the first time I started to wonder if tree planting might someday become ecologically unviable in some regions of the province.

The lack of precipitation coupled with unseasonably high temperatures made the soil on some blocks so dry and compacted it was like planting into a sheet of rock. I was often struck with the sense that the earth was actively rejecting the trees I was planting. I imagined the trees I’d planted withering and dying, eventually becoming fuel for the wildfires that were then burning all around us.

Was it possible that these intensifying climatic events could render some ecosystems unable to support the growth of new trees? Was I on the frontlines of witnessing the beginning of the end of reforestation as we’ve known it for the last 50 years?

I decided to ask around. I spoke to Sally Enns, who works as a forestry manager contracted by the Cheslatta Carrier Nation and is an incoming supervisor at the reforestation company I work for; we were based out of the same bush camp for part of last season. Reflecting on the drought conditions, she articulated many of the same concerns that I’d had.

Jet fuel can’t melt silica sheets.

While I am memeing, it’s highly doubtful that the A, B, and C master horizons are being ‘burnt off’, due to their mineral nature. I could see the lack of veg causing these soils to be highly prone to erosion though, with subsequent soil losses during rainfall events.

Some forests have Folisols (organic soils comprised entirely of fallen detritus), but those are not the dominant soil order in BC (typical it’s brunsiols and regosols).

I am also not surprised at the resilience of the seedlings. In most reveg plans, we account for 20% mortality.

Finally, if you want to see what impact climate change may have on the ecosystems of BC, you can see it here:

https://cfcg.forestry.ubc.ca/projects/climate-data/climatebc-and-bioclimatic-envelope-modelling/