Here is the study in English (pdf). There is a Hungarian version on website.

If you seek some orientation which political parties belong to which group in the EP, you may find this link to the European Parliament helpful.

Although most delegations from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) are highly critical of the Kremlin, China and other authoritarian countries in the European Parliament, there are significant differences among them, a new study published by Political Capital reveals.

The Hungarian institute teamed up with partners to track the views of incumbent MEPs from the Visegrad countries, Austria, Bulgaria and Romania on authoritarian regimes.

While the Polish and Czech mainstream parties are staunch critics of authoritarians in the international and domestic arena, other mainstream parties from Austria, Bulgaria, and Romania are not as committed at home. Some populist radical and far-right parties seem to be close friends of authoritarians. Some parties such as Hungary’s Fidesz, Slovakia’s SMER-SD and Bulgaria’s BSP can be considered “soft defenders”. These parties engage in discourse similar to the far right, but intentionally abstain from voting due to political and reputational risks.–

As the European Parliament’s ninth term (2019-2024) is drawing a close, we can say that Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) have faced unprecedented challenges from Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and reacted to an increasingly assertive China that is now threatening Taiwan openly. While the European Parliament (EP) has no real decision-making power in the field of foreign policy, the interferences of authoritarian states show that their word still matters on the world stage. The alleged cash-for-influence Qatargate scandal, the biggest corruption instance to hit the EU in decades, showcased that authoritarian states are willing to spend resources on buying influence in the Parliament and its committees. Consequently, there is ever-growing value in studying the foreign policy-related votes in the EP.

Although the EP is not able to shape the EU’s foreign policy by itself, it can exert influence over it through its resolutions. Our previous study demonstrated that the MEPs have achieved substantive results in influencing the Union’s foreign policy decisions, such as voting to freeze the ratification of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement and approving the Ukraine Facility to help fund Ukraine in its struggle against Russia. The EP can exert more significant influence through the co-decision procedure as its consent or approval is necessary for issues like new EU Member State accession and international trade deals. The incoming MEPs in the next EU Parliament can be at least as influential in shaping the EU’s policies towards third countries as their predecessors were if the critics of authoritarian regimes maintain their substantial majority. Our analysis examines which parties consistently criticize authoritarian countries in the EP, from Austria, Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia.

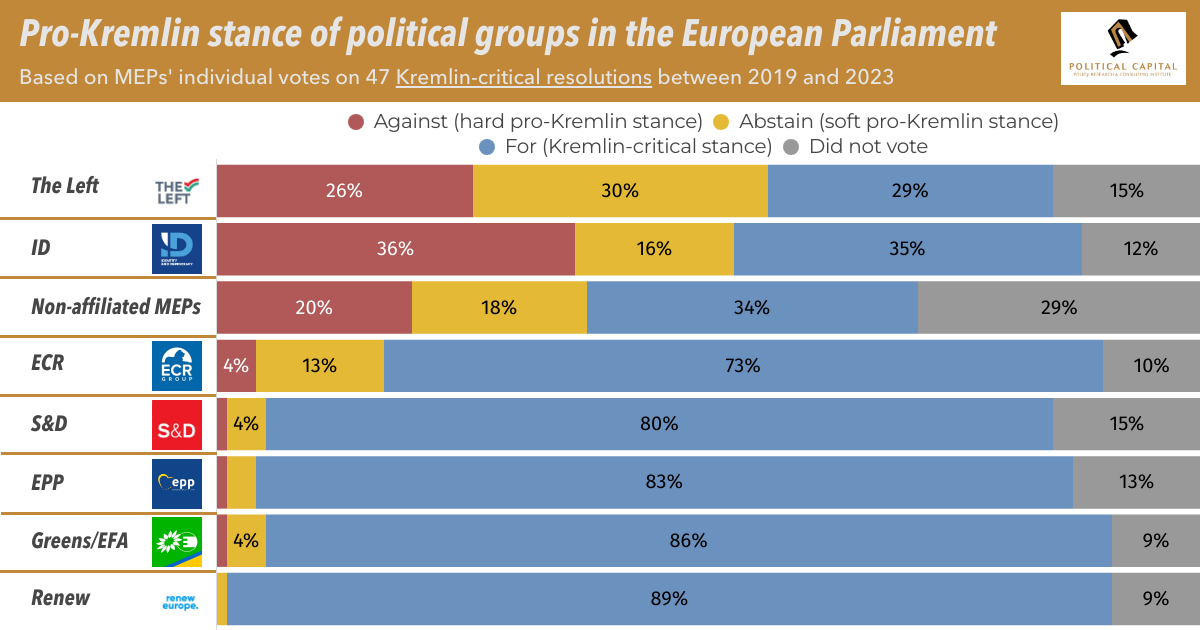

Big Picture: Party groups’ attitudes towards the Kremlin, China and other authoritarians

Bulwark against authoritarianism

The majority of MEPs from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) are highly critical of the Kremlin, China, and other authoritarian regimes. This CEE “bulwark” against authoritarian countries varies between countries; the mainstream parties from Austria, Bulgaria, Czechia, Poland and Romania, as well as opposition parties from Hungary and Slovakia, are the toughest on authoritarianism. However, the authoritarian-critical voting stances may reflect concerns with social desirability within the European arena (as well as the convictions of individual MEPs). In Austria, Bulgaria and Romania, domestic party-political stances have pointed to more equivocal dispositions towards authoritarian regimes over time due to geopolitical positions and political and economic goals.

The Czech and Polish mainstream parties are the regional strongholds against authoritarian states. The Polish society and the whole political class share deep-rooted anti-Kremlin sentiment that transpires into the Polish MEPs’ behavior in the EP. None of the Polish MEPs voted against any of the Russia-related votes. The ruling coalition parties and the Law and Justice (PiS, ECR) also united against Beijing due to widespread anti-communist and pro-American sentiments. Similarly, the Czech ruling coalition parties and the largest opposition party, ANO (RE), are jointly committed to critical stances towards authoritarianism. Czech MEPs continue to follow the value-based tradition of Vaclav Havel’s diplomacy, which underscores the protection of human rights. At the same time, ANO has diverged from this strong Kremlin critical behavior and willfully spread anti-Ukrainian narratives at home. While Czech politicians show signs of pragmatism in relations with China, they do not shy away from condemning the country for its human rights violations in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Xinjiang, underlying that human rights are pre-conditions for engaging in trade and investment.

Although Austrian, Bulgarian and Romanian parties tend to support resolutions against the Kremlin, China, and other authoritarian countries in the EP their domestic representatives are not as committed to a staunch critical stance. There is a substantial disparity between domestic and international discourse. While the MEPs of the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP, EPP) condemn authoritarians along with the rest of the mainstream parties in the EP (Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ, S&D), Greens (Greens/EFA), and the New Austria and Liberal Forum (NEOS, RE)), the ÖVP-led government engaged in a more pragmatic discourse at home and even blocked Kremlin critical initiatives within the EU institutions. Similarly, Romanian MEPs are more in with the open criticism of Moscow and Beijing than domestic representatives. Likewise, the conservative Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, EPP) and the liberal Movement for Rights and Freedom (DPS, RE) consistent alignment with critical attitudes towards Russia and China in the EP may be hollow. GERB’s and MRF’s strict adherence to critical resolutions on the surface may hide their deep-seated attitudes and behaviors favorable to Russian and Chinese interests.

Opposition parties from Slovakia and Hungary generally support resolutions that condemn the policies of authoritarian states. The Slovak MEPs from center and center-right parties (Progressive Slovakia (PS, RE), Christian Democratic Movement (KDH, EPP)Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO, EPP), Freedom and Solidarity (SaS, ECR), Democrats (former Spolu-OD, RE) have sharply critical attitudes towards authoritarian regimes. While Hungarian opposition MEPs (Democratic Coalition (DK, S&D), Momentum (RE), Jobbik-Conservatives, Independent) show resistance to authoritarianism, they miss numerous votes compared to Western parties. One notable figure here is István Ujhelyi, who missed 73% of the votes concerning China, likely exhibiting a “soft defense” strategy towards China. The DK and the Jobbik-Conservatives have become critical of Russia in the past few years as these parties used to have close ties with the Kremlin: DK leader Ferenc Gyurcsány pursued a very pro-Russian foreign policy line as prime minister before 2009, while the then-extremist Jobbik party promoted the Kremlin’s policy goals and legitimized the Russian regime before the party’s mainstream turn starting around 2016.

Friends of authoritarians

There are some parties from the CEE that seem to be lenient towards authoritarians. These are mostly extremist fringe parties such as the Freedom and Direct Party (SPD, ID), the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM, The Left) from Czechia, and the Slovak Republic Movement (Republika, Independent) and the Slovak Patriot (Independent). The only exception is the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ, ID), which has been leading the polls in Austria. These parties can be deemed as the main entry points for authoritarian regimes to influence EP resolutions, although their aggregated weight is too low for any chance of success.

The FPÖ has cultivated a notoriously friendly relationship with the Kremlin and even signed a “friendship” agreement with the Russian ruling party, United Russia, in 2016. The FPÖ MEPs failed to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in key votes and statements. For instance, they voted against establishing the Ukraine Facility. The party also questioned the EU sanctions levied on Russia and called for a referendum on the matter in Austria. The leader of the FPÖ delegation, MEP Harald Vilimsky, stressed that a “small clique of EU-centralists is endangering our prosperity and freedom” with these sanctions.

Soft defenders of China and Russia

Some parties are “soft defenders” of Russia and other authoritarian regimes. We can call the strategy of the Hungarian right-wing Fidesz (Independent), the left-wing Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP, S&D) and Direction – Slovak Social Democracy (Smer-SD, Independent) on foreign policy votes as “soft defense”; meaning that frequently, these parties seem to miss votes deliberately to avoid having to condemn authoritarian regimes. Notably, the parties’ representatives engage in a discourse similar to that of far-right parties such as the FPÖ, while withdrawing from the voting process, presumably out of concern for the geopolitical risks and reputational costs of openly supporting Russia and China.

The Fidesz MEPs seem to intentionally abstain from voting, which condemns countries that are friendly to the Hungarian government. They missed more votes on issues relevant to Russia than the number of Kremlin-critical votes they cast. They voted critically on Russia 194 times altogether but failed to cast any vote 220 times. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the MEPs abstained more often and even started to vote against resolutions condemning the Kremlin. Alarmingly, they failed to vote on a resolution condemning Russia for its unprovoked, unjustifiable war of aggression against Ukraine, as well as Belarus’ alliance with Russia, on the occasion of the anniversary of the invasion. As a consequence of this strategy, Fidesz falls between the attitude of ECR and ID concerning Russia and China. Depending on whether Fidesz ends up in ID or ECR after the 2024 EP election determines whether the party openly becomes a friend of authoritarians or engages in a slightly more critical stance.

Like Fidesz, a distinctive pattern emerges in BSP MEPs’ voting behavior: the non-participation or abstention from voting on resolutions that condemn authoritarian states’ actions. The BSP MEPs voted against Russia-related resolutions 15 times, abstained 16 times and failed to cast any vote 111 times. Consequently, the MEPs can conceal and subdue their Russia-friendly stances via non-voting while supporting a few resolutions that condemn the most outrageous Russian interferences. While they supported the resolution on Russian aggression on Ukraine in 2022, they abstained from voting on the resolution that marked one year of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Although BSP MEPs showed a tougher stance against China, they did not participate in Beijing’s critical resolutions 40 times and abstained 10 times. The party’s behaviour calls into question the extent to which the BSP – the formal successor to the Bulgarian Communist Party- integrated pro-Western and democratic values. The party continues to be divided between pro-Russian traditionalist-nationalist and pro-European fractions.

Although Smer-SD MEPs showed a more critical attitude towards authoritarianism than Fidesz and BSP, they frequently abstained in relevant votes and voted against pro-democratic resolutions. In October 2023, the party’s membership was suspended in the S&D group due to SMER-SD MEPs coalescing with the radical right. Smer-SD MEPs voted against the Report on the direction of EU-Russia political relations that strongly criticised Russia. The MEPs portray Russia as a reliable international partner and a friendly state in key debates. Growing threat in the next term

The CEE bulwark against authoritarianism may weaken in the EP after the upcoming 2024 elections. Extremist parties like the FPÖ stand to gain more EP seats, while new far-right and pro-Kremlin ones, such as the Hungarian Our Homeland (Mi Hazánk) and the Bulgarian Revival (Vazrazhdane), are likely to join the Parliament. Along with the deterioration of the mainstream parties, these far-right parties will certainly erode the EP’s resolve against authoritarian regimes, as there will be more entry points for authoritarian countries to influence the decision-making. However, it remains unlikely that these parties will be able to turn the EP into a dovish body from its current hawkish foreign policy approach.

Additionally, there should be cause for alarm in the Council of the EU. Fidesz, Smer-SD, BSP and, to a lesser extent, ÖVP seem to be very lenient toward authoritarian countries. Fidesz, Smer-SD and ÖVP are the ruling parties in their respective countries. Thus, the Kremlin’s, China’s or other malign regimes’ interference can be reflected in EU policies via these parties through their work in the Council. Meanwhile, BSP remains the main opposition party in Bulgaria.

Oh no, our poor economy, better let them murder people in Ukraine unpunished instead of trying everything to stop not just them but also everyone else like China.