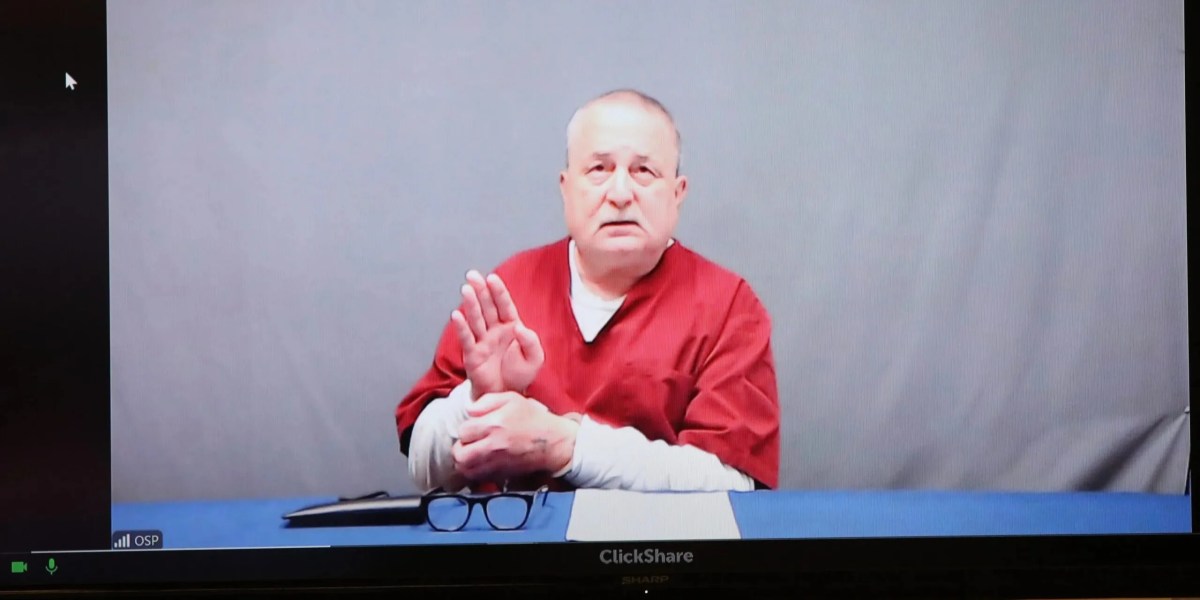

RICHARD ROJEM JR. had 20 minutes to address the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board. Wearing a maroon prison uniform, he raised his cuffed right hand and swore to tell the truth, then gave his pitch for why his life should be spared. It would take less than 90 seconds.

“This hearing didn’t have to take place,” he began. Prosecutors had offered a plea deal right up until the day of his 1985 trial; if he’d admitted to abducting, raping, and murdering his young stepdaughter, Layla Cummings, Rojem could have avoided a death sentence. But he refused: “An innocent man doesn’t ever plead guilty to a crime he hasn’t committed.”

Rojem spoke via video link from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. It was June 17, and his execution was 10 days away. At 66, he’d been on death row for virtually his whole adult life. He’d survived for so long in part because appellate courts had deemed his original trial to be unfair, upholding his conviction but twice overturning his death sentence. Meanwhile, fingernail scrapings taken from Cummings revealed an unknown male DNA profile and nothing from Rojem. This was potentially powerful exculpatory evidence. But a third jury, unaware of the DNA testing, resentenced him to die.

If a sentencing judge gives someone the death penalty they should be willing to put their own life on the line. If, after the fact, the person is exonerated, execute the judge.

This is how you make sure nobody gets exonerated ever