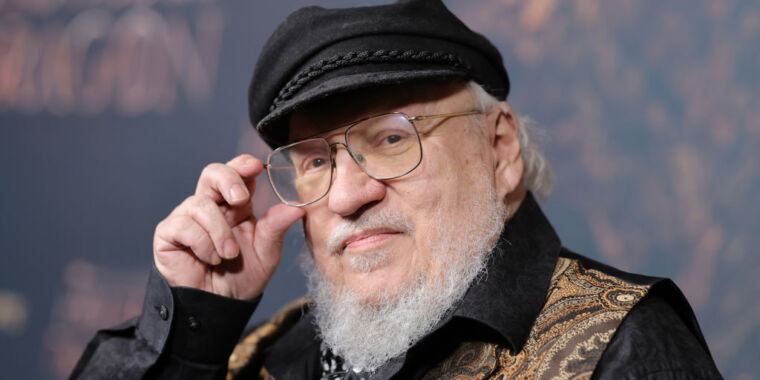

Yesterday, popular authors including John Grisham, Jonathan Franzen, George R.R. Martin, Jodi Picoult, and George Saunders joined the Authors Guild in suing OpenAI, alleging that training the company’s large language models (LLMs) used to power AI tools like ChatGPT on pirated versions of their books violates copyright laws and is “systematic theft on a mass scale.”

“Generative AI is a vast new field for Silicon Valley’s longstanding exploitation of content providers," Franzen said in a statement provided to Ars. "Authors should have the right to decide when their works are used to ‘train’ AI. If they choose to opt in, they should be appropriately compensated.”

OpenAI has previously argued against two lawsuits filed earlier this year by authors making similar claims that authors suing “misconceive the scope of copyright, failing to take into account the limitations and exceptions (including fair use) that properly leave room for innovations like the large language models now at the forefront of artificial intelligence.”

This latest complaint argued that OpenAI’s “LLMs endanger fiction writers’ ability to make a living, in that the LLMs allow anyone to generate—automatically and freely (or very cheaply)—texts that they would otherwise pay writers to create.”

Authors are also concerned that the LLMs fuel AI tools that “can spit out derivative works: material that is based on, mimics, summarizes, or paraphrases” their works, allegedly turning their works into “engines of” authors’ “own destruction” by harming the book market for them. Even worse, the complaint alleged, businesses are being built around opportunities to create allegedly derivative works:

Businesses are sprouting up to sell prompts that allow users to enter the world of an author’s books and create derivative stories within that world. For example, a business called Socialdraft offers long prompts that lead ChatGPT to engage in ‘conversations’ with popular fiction authors like Plaintiff Grisham, Plaintiff Martin, Margaret Atwood, Dan Brown, and others about their works, as well as prompts that promise to help customers ‘Craft Bestselling Books with AI.’

They claimed that OpenAI could have trained their LLMs exclusively on works in the public domain or paid authors “a reasonable licensing fee” but chose not to. Authors feel that without their copyrighted works, OpenAI “would have no commercial product with which to damage—if not usurp—the market for these professional authors’ works.”

“There is nothing fair about this,” the authors’ complaint said.

Their complaint noted that OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman claims that he shares their concerns, telling Congress that "creators deserve control over how their creations are used” and deserve to “benefit from this technology.” But, the claim adds, so far, Altman and OpenAI—which, claimants allege, “intend to earn billions of dollars” from their LLMs—have “proved unwilling to turn these words into actions.”

Saunders said that the lawsuit—which is a proposed class action estimated to include tens of thousands of authors, some of multiple works, where OpenAI could owe $150,000 per infringed work—was an “effort to nudge the tech world to make good on its frequent declarations that it is on the side of creativity.” He also said that stakes went beyond protecting authors’ works.

“Writers should be fairly compensated for their work,” Saunders said. "Fair compensation means that a person’s work is valued, plain and simple. This, in turn, tells the culture what to think of that work and the people who do it. And the work of the writer—the human imagination, struggling with reality, trying to discern virtue and responsibility within it—is essential to a functioning democracy.”

The authors’ complaint said that as more writers have reported being replaced by AI content-writing tools, more authors feel entitled to compensation from OpenAI. The Authors Guild told the court that 90 percent of authors responding to an internal survey from March 2023 “believe that writers should be compensated for the use of their work in ‘training’ AI.” On top of this, there are other threats, their complaint said, including that “ChatGPT is being used to generate low-quality ebooks, impersonating authors, and displacing human-authored books.”

Authors claimed that despite Altman’s public support for creators, OpenAI is intentionally harming creators, noting that OpenAI has admitted to training LLMs on copyrighted works and claiming that there’s evidence that OpenAI’s LLMs “ingested” their books “in their entireties.”

“Until very recently, ChatGPT could be prompted to return quotations of text from copyrighted books with a good degree of accuracy,” the complaint said. “Now, however, ChatGPT generally responds to such prompts with the statement, ‘I can’t provide verbatim excerpts from copyrighted texts.’”

To authors, this suggests that OpenAI is exercising more caution in the face of authors’ growing complaints, perhaps since authors have alleged that the LLMs were trained on pirated copies of their books. They’ve accused OpenAI of being “opaque” and refusing to discuss the sources of their LLMs’ data sets.

Authors have demanded a jury trial and asked a US district court in New York for a permanent injunction to prevent OpenAI’s alleged copyright infringement, claiming that if OpenAI’s LLMs continue to illegally leverage their works, they will lose licensing opportunities and risk being usurped in the book market.

Ars could not immediately reach OpenAI for comment. [Update: OpenAI’s spokesperson told Ars that “creative professionals around the world use ChatGPT as a part of their creative process. We respect the rights of writers and authors, and believe they should benefit from AI technology. We’re having productive conversations with many creators around the world, including the Authors Guild, and have been working cooperatively to understand and discuss their concerns about AI. We’re optimistic we will continue to find mutually beneficial ways to work together to help people utilize new technology in a rich content ecosystem.”]

Rachel Geman, a partner with Lieff Cabraser and co-counsel for the authors, said that OpenAI’s "decision to copy authors’ works, done without offering any choices or providing any compensation, threatens the role and livelihood of writers as a whole.” She told Ars that "this is in no way a case against technology. This is a case against a corporation to vindicate the important rights of writers.”

Funny, but I don’t think there’s a very strong argument that training AI is fair use, especially when you consider how it intersects with the standard four factors that generally determine whether a use of copyrighted work is fair or not.

Specifically stuff like:

(Keep in mind that many popular AI models have been trained on vast amounts of entire artworks, large sections of text, etc.)

To me, this factor is by far the strongest argument against AI being considered fair use.

The fact is that today’s generative AI is being widely used for commercial purposes and stands to have a dramatic effect on the market for the same types of work that they are using to train their data models–work that they could realistically have been licensing, and probably should be.

Ask any artist, writer, musician, or other creator whether they think it’s “fair” to use their work to generate commercial products without any form of credit, consent or compensation, and the vast majority will tell you it isn’t. I’m curious what “strong argument” that AI training is fair use is, because I’m just not seeing it.

AI training is taking facts which aren’t subject to copyright, not actual content that is subject to it. The original work or a derivative isn’t being distributed or copied. While it may be possible for a user to recreate a copyrighted material with sufficient prompting, the fact it’s possible isn’t any more relevant than for a copy machine. It’s the same as an aspiring author reading all of Martin’s work for inspiration. They can write a story based on a vaguely medieval England full of rape and murder, without paying Martin a dime. What they can’t do is call it Westeros, or have the main character be named Eddard Stork.

There may be an argument that a copy needs to be purchased to extract the facts, but that’s not any special license, a used copy of the book would be sufficient.

AI isn’t doing anything that hasn’t already been done by humans for hundreds of years, it’s just doing it faster.

This isn’t about a person reading things and taking inspiration and writing a similar story though. This is about a company consuming copyrighted works to and selling software that is built on those copyrighted works and depends on those copyrighted works. It’s different.

A company is just a person in the legal world. They are consuming copyrighted works just like an aspiring author. They are then using that knowledge to generate something new.

Legally, I think you’re basically right on.

I think what will eventually need to happen is society deciding whether this is actually the desired legal state of affairs or not. A pretty strong argument can be made that “just doing it faster” makes an enormous difference on the ultimate impact, such that it may be worth adjusting copyright law to explicitly prohibit AI creation of derivative works, training on copyrighted materials without consent, or some other kinds of restrictions.

I do somewhat fear that, in our continuous pursuit for endless amounts of convenient “content” and entertainment to distract ourselves from the real world, we’ll essentially outsource human creativity to AI, and I don’t love the idea of a future where no one is creating anything because it’s impossible to make a living from it due to literally infinite competition from AI.

I think that fear is overblown, ai models are only as good as their training material. It still requires humans to create new content to keep models growing. Training ai on ai generated content doesn’t work out well.

Models aren’t good enough yet to actually fully create quality content. It’s also not clear that the ability for them to do so is imminent, maybe one day it will. Right now these tools are really onlyngood for assisting a creator in making drafts, or identifying weak parts of the story.

Which is why I really hate the fact that the programmers and the media have dubbed this “intelligence”. Bigger programs and more data doesn’t just automatically make something intelligent.

This is such a weird take imo. We’ve been calling agent behavior in video games AI since forever but suddenly everyone has an issue when it’s applied to LLMs.

If I took 100 of the world’s best-selling novels, wrote each individual word onto a flashcard, shuffled the entire deck, then created an entirely new novel out of that, (with completely original characters, plot threads, themes, and messaged) could it be said that I produced stolen work?

What if I specifically attempted to emulate the style of the number one author on that list? What if instead of 100 novels, I used 1,000 or 10,000? What if instead of words on flashcards, I wrote down sentences? What if it were letters instead?

At some point, regardless of by what means the changes were derived, a transformed work must pass a threshold whereby content alone it is sufficiently different enough that it can no longer be considered derivative.

Y’all are missing the point, what you said is about AI output and is not the main issue in the lawsuit. The lawsuit is about the input to AI - authors want to choose if their content may be used to train AI or not (and if yes, be compensated for it).

There is an analogy elsewhere in this thread that is pretty apt - this scenario is akin to an university using pirated textbooks to educate their students. Whether or not the student ended up pursing a field that uses the knowledge does not matter - the issue is the university should not have done so in the first place (and remember, the university is not only profiting off of this but also saving money by shafting the authors).

I imagine that the easiest way to acquire specific training data for a LLM is to download EBooks from amazon. If a university professor pirates a textbook and then uses extracts from various pages in their lecture slides, the cost of the crime would be the cost of a single textbook. In the case of a novel, GRRM should be entitled to the cost of a set of Ice & Fire if they could prove that the original training material was illegaly pirated instead of legally purchased.

Once a copy of a book is sold, an author typically has no say in how it gets used outside of reproduction.

I’m not sure your assessment of the “cost of damages” is really accurate but again, that’s not the point.

The point of the lawsuit is about control. If the authors succeed in setting precedent that they should control the use of their work in AI training, then they can easily negotiate the terms with AI tech companies for much more money.

The point of the lawsuit is not one-time compensation, it’s about the control in the future.