The only drug that treats syphilis during pregnancy is in short supply. Untreated, the disease can pass to newborns, killing them or leaving them with disabilities. As cases rise sharply, the government isn’t doing much to prevent shortages.

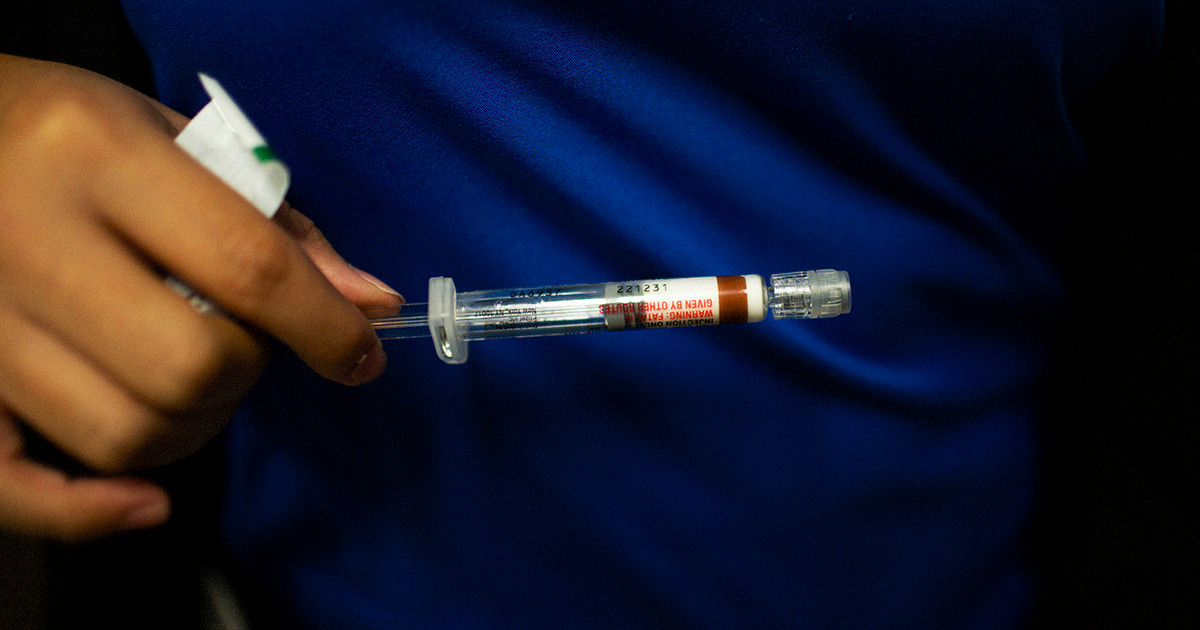

Karmin Strohfus, the lead nurse at a South Dakota jail, punched numbers into a phone like lives depended on it. She had in her care a pregnant woman with syphilis, a highly contagious, potentially fatal infection that can pass into the womb. A treatment could cure the woman and protect her fetus, but she couldn’t find it in stock at any pharmacy she called — not in Hughes County, not even anywhere within an hour’s drive.

Most people held at the jail where Strohfus works are released within a few days. “What happens if she gets out before I’m able to treat her?” she worried. Exasperated, Strohfus reached out to the state health department, which came through with one dose. The treatment required three. Officials told Strohfus to contact the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for help, she said. The risks of harm to a developing baby from syphilis are so high that experts urge not to delay treatment, even by a day.

Nearly three weeks passed from when Strohfus started calling pharmacies to when she had the full treatment in hand, she said, and it barely arrived in time. The woman was released just days after she got her last shot.

Last June, Pfizer, the lone U.S. manufacturer of the injections, notified the Food and Drug Administration of an “impending stock out” that it anticipated would last a year. The company blamed “an increase in syphilis infection rates as well as competitive shortages.”

What the hell is “competitive shortages”?