- cross-posted to:

- creative@beehaw.org

- cross-posted to:

- creative@beehaw.org

I was asked by a lemmy user to write up a summary of how stones are cut. This post is my attempt at sharing what I know and how I cut. I do this as a hobby and am by no means an expert, so I’m sure there are techniques and such that I don’t cover.

Designs

You can’t cut a stone without a design of some kind.

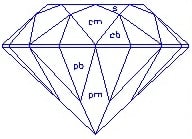

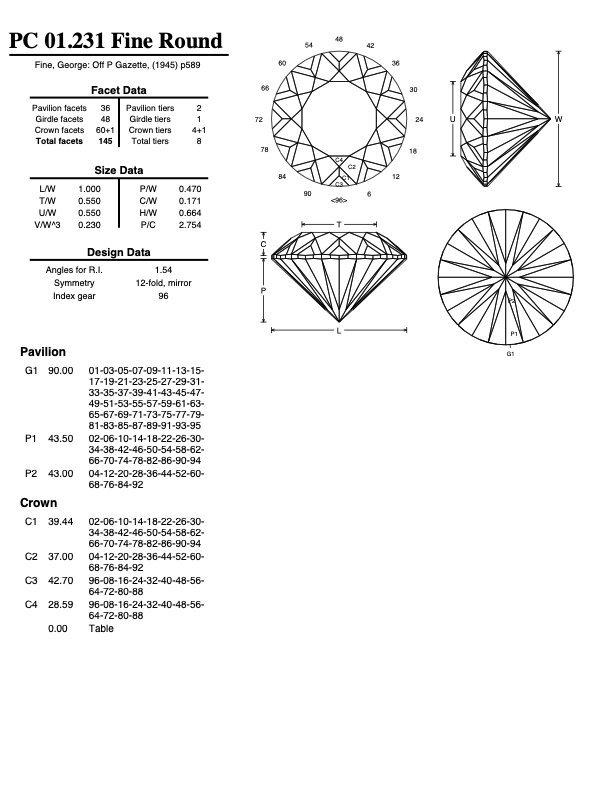

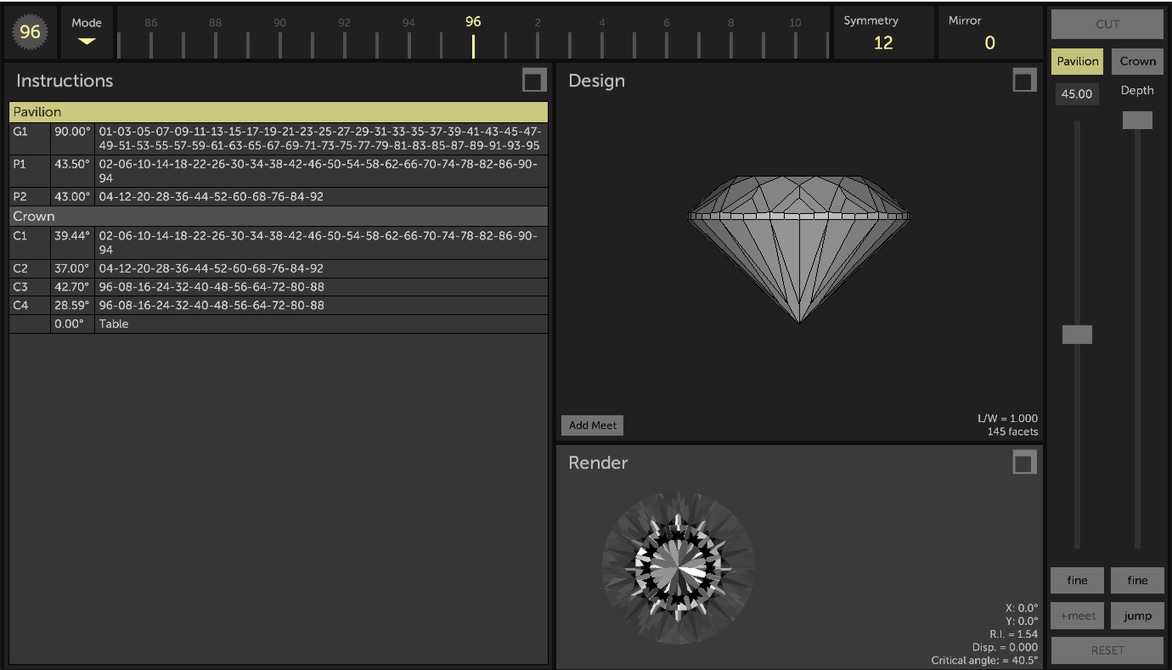

A cut stone is typically divided in two halves: pavilion (bottom) and crown (top). Each half has a set of tiers that that are differentiated by the angle they are cut. In the design above there are three tiers in the pavilion and four tiers in the crown. Within each tier each facet is defined by the index, a number that indicates a position around the circumference of the stone.

The angle for each tier is important to the overall stone’s color and light return due to each type of stone’s R.I. (refractive index) value. The refractive index indicates the deflection light takes when it enters the stone.

In the past many designs were done by hand using math, but these days there is great cad software that allows a cutter to create their own unique designs.

Even with the CAD software, there is still the need to understand a great deal about how light interacts with a stone to achieve that perfect design.

Cutting Machine

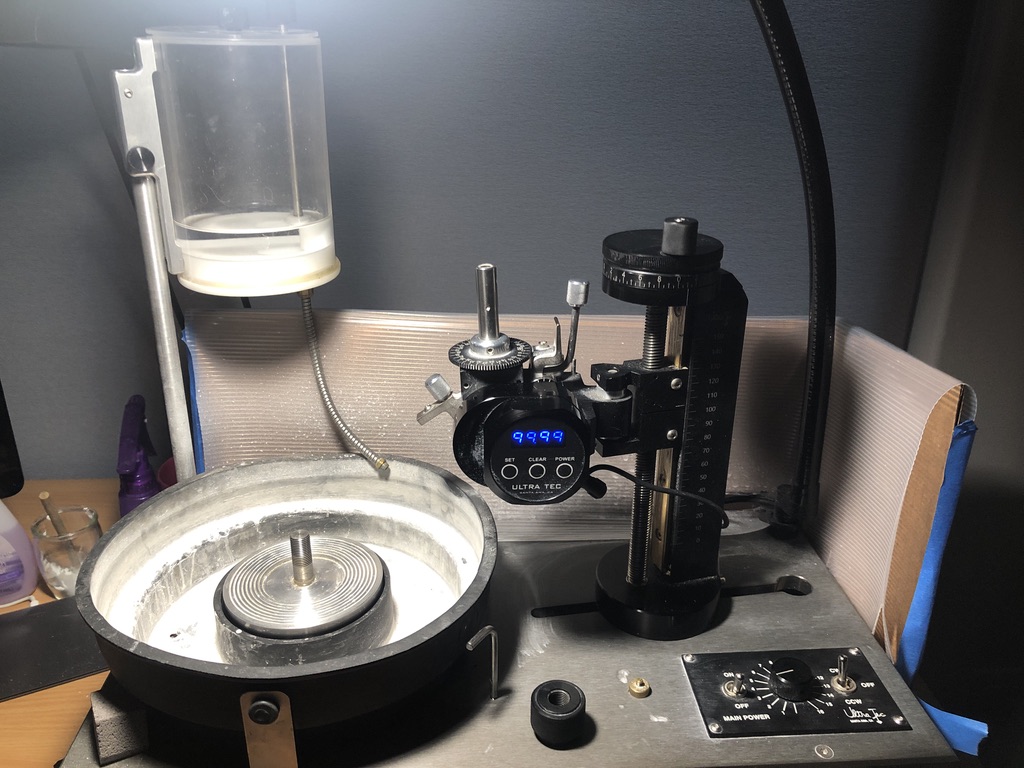

There are three major types of cutting machines: mast, hand piece and jam peg. In this post I’m only going to cover the mast type, as that’s what I use.

Mast

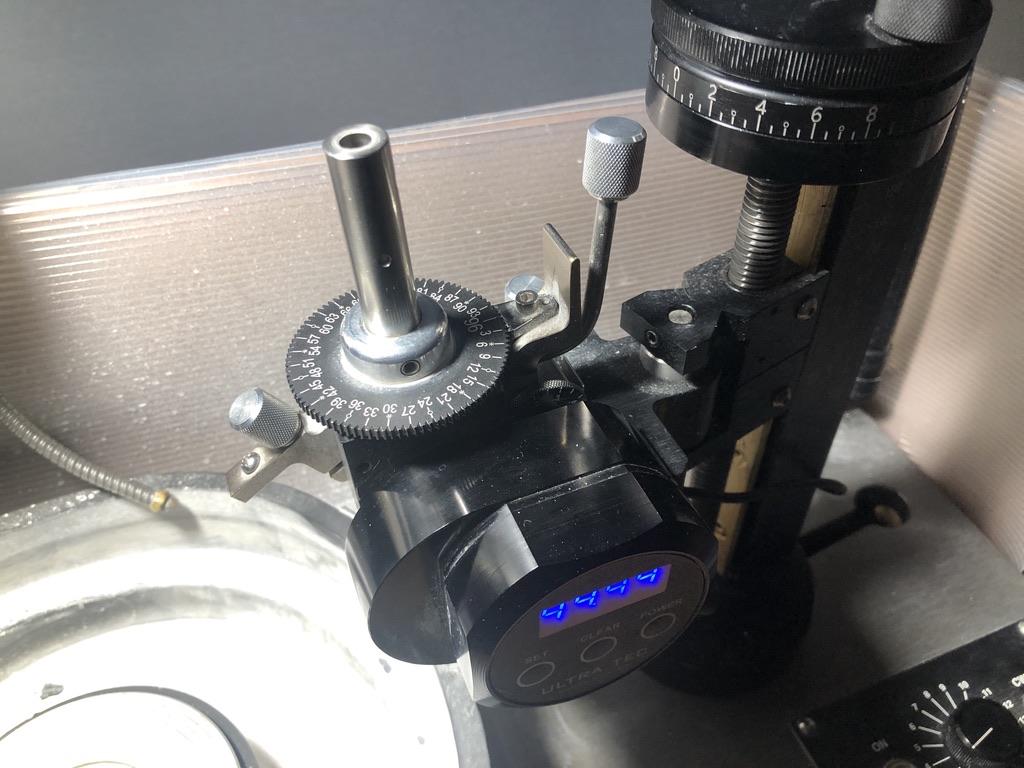

The mast allows for fine adjustment of the depth of the cut using the knob and wheel at the top. This control moves the cutting head up or down against the cutting surface.

Cutting Head

The cutting head holds the stone and allows for two different positional adjustments.

Index

The index of the stone is the position around the circumference of the stone as defined by the index gear.

There are additional index gears that can be put on the machine with the highest running 120 index positions.

Angle

The cutting head can be adjusted to specific angles as defined by the design. For this machine, the accuracy of the angle is 0.01 degrees.

Base

The base of the machine contains the motor, speed controls, splash guard and water drip tank.

Additional Equipment

Dops

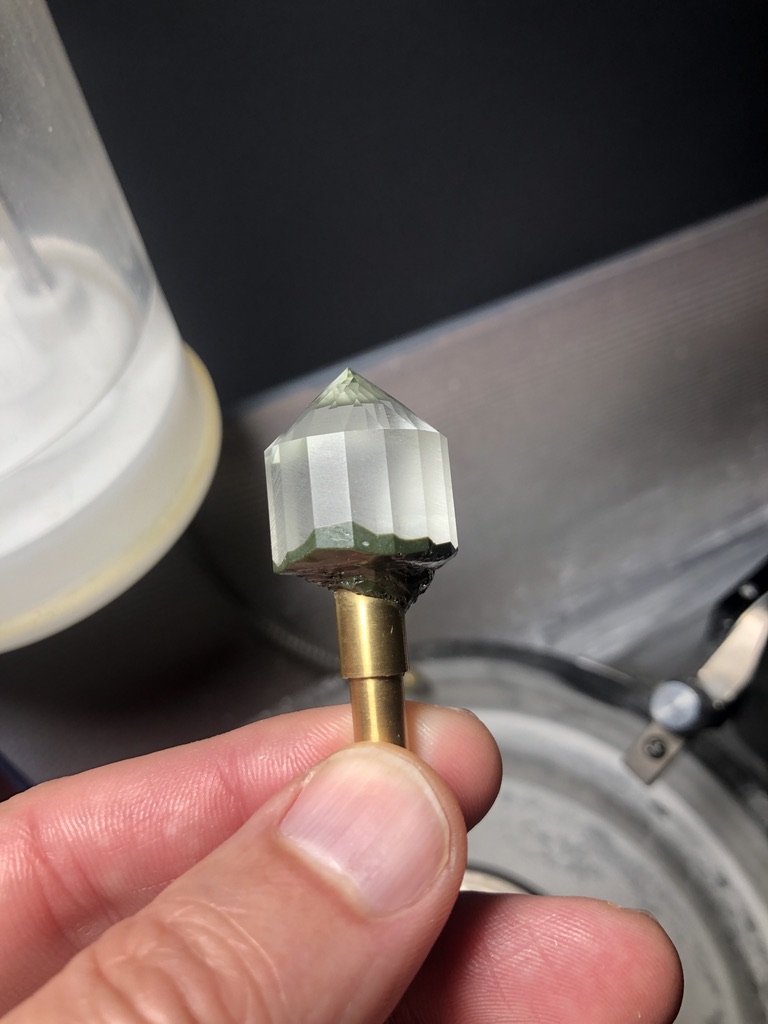

A dop is a brass rod that stone is attached to, either by glue or wax, and fits into the cutting head.

Waxed on stone

Glued on stone

Laps

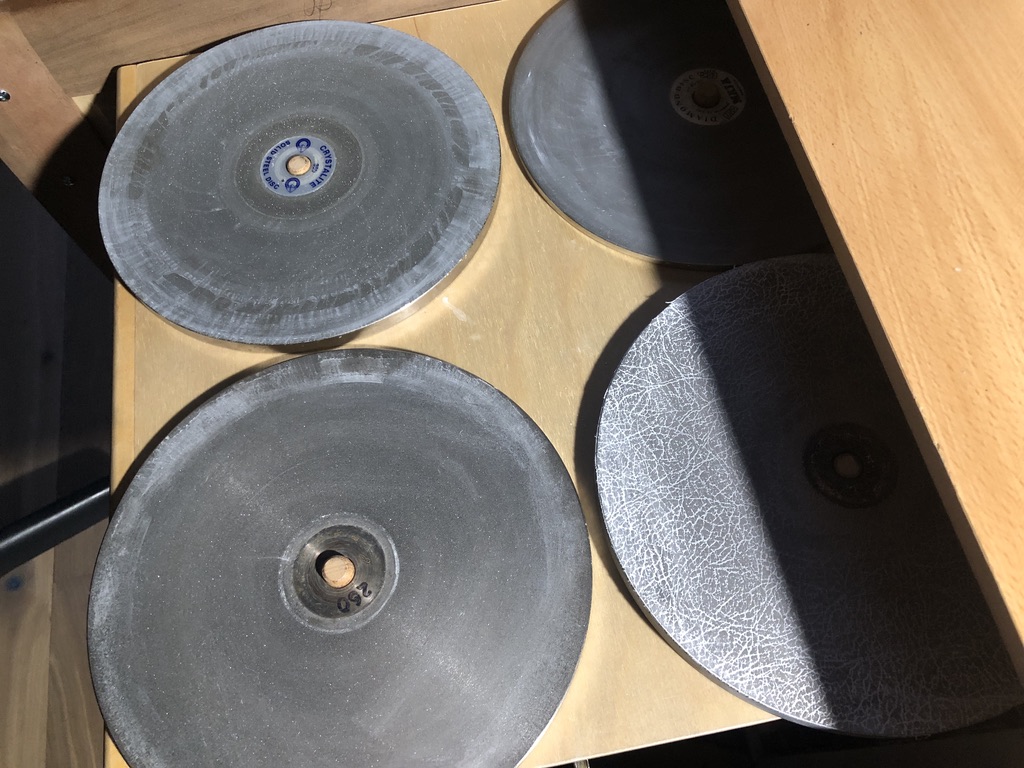

A lap is the actual cutting surface that fits onto the spindle on the machine’s base.

Laps come in a variety of grits: 260, 600, 1200, 3000 (pre-polish) etc. For polish I use a 60,000 grit diamond paste on a tin lap. When working with laps, cross contamination of laps from lower to higher grits can cause scratches when trying to pre-polish or polish, so keeping them clean is important.

The Cutting Process

Rough Stones

First things first, I pick out a piece of rough and look at it closely.

In the above image, the rough from left to right are:

- Amethyst

- Montana Sapphire (Yes Montana has sapphires!)

- Topaz

- Apatite

- Morganite (nice peach color)

What I do is look at the existing shape of the rough as well as any inclusions or fractures within the stone in order to attempt to determine the shape I’ll cut the stone into in order to maximize the yield. Generally a cutter will lose 50% (less likely) to 60% or more of the original stone.

Pre-form or Rough in

This step is all about creating the rough shape of the stone. For example, if I am going to create a round stone I’ll form the stone into a rough cylinder using my hands against the lowest grit lap spinning at a moderate speed. I may also use a saw attachment to slice off a portion if the optimal usage of the original material dictates I can save and use it. Additionally I may hand rough in a general pavilion shape to speed up the cutting process later.

The final step is to flatten one end of the cylinder to act as a starting point for the table (flat top facet on the crown). This serves two purposes:

- Clean point to glue to the dop

- If the stone pops off the dop during cutting it can be realigned vertically using that same surface.

Attaching the Stone to a Dop

What I use for gluing a stone to a dop has changed over the years. I used to use a very hard wax that I would heat up and attach to the dop and stone. I still do this for smaller stones, as it provides me the ability to readjust the stone on the dop until I’m happy with it. For medium and larger stones I use super glue and have gotten pretty good at aligning the stone quickly before the glue hardens.

Cutting the stone

I was going to describe how I would cut the above design, but instead what I’m going to do is start a new stone from scratch. I’ll post a series of posts with images and descriptions of the steps I’m performing to give all of you a good idea of the entire process I use from start to finish.

This is such an interesting and weird hobby to have. Thanks for taking the time to write up this explanation. I’ve always wondered how this was done. How did you get into cutting stones as a hobby? It seems like the barrier to entry is incredibly high.

(copy and pasted from another reply I made in another post)

So my mom was a geologist and brought home many cool specimens and even tried cutting herself, but she didn’t have the knack or patience for it. I’ve always been a hands on type of person, so I decided to give it a shot. I was taught by a Japanese woman in Maryland who did commission work for high end custom jewelry stores in the Washington D.C. area. That was while I was in high school and the machine I used was not nearly as accurate as I’m using today.

I’ve been cutting off and on for decades now, and it’s just a hobby for me. There are others I know that do this for a living, so I know it’s possible. The big issue around being profitable is the influx of poorly cut stones at cheap prices. To make a living you need to produce stones that are remarkable, and create a reputation that makes your stones desirable. It’s amazing how I can go into a typical jewelry store and see stone after stone with bad symmetry, windowed or even fish eye cuts with high prices. I do take a commission here and there, but I mostly do this for the pure enjoyment it brings creating something of beauty, as well as giving results to family and friends.

There are three ways you could get started with this:

- Find a local lapidary club in your area and see if they have any classes.

- Find a cutter that is local to you that would be willing to teach you.

- Teach yourself. (This is the riskier approach)

For 1 and 2, find custom jewelry stores in your area that have a certified gemologist on staff, and have a chat with them. They will likely have knowledge of who is around your area. Be forewarned though, there are large cities where there are NO cutters or active lapidary clubs.

Finally, this is NOT a cheap hobby. The equipment alone, for a really good setup, can set you back $6-$7k without the actual rough to cut. You can get cheaper machines and possibly used ones, but you need to be careful that they are either not damaged or so cheap that they don’t cut accurately. If it doesn’t cut accurately you’ll get incredibly frustrated at your results.

Very cool, glad you had someone to teach you this amazing art form. And thanks for sharing your creations with us all. Are there low value gems that you practice on before cutting more expensive ones? In your post you talked about refractive index of the gem itself, does that really vary between gem types enough to make certain gems react different to certain designs?

For cuts I’ve never tried before I’ll always practice with a form of quartz (clear, smoky or amethyst).

Many of the cuts work well for most stone types, but not all. For example, my “iris” cut which I posted in the community looks great in a number of stone types, but in deeply saturated types like garnet you don’t get the expected light return pattern.

In other types like diamond, CZ with a higher refractive index you get far more light return which washes out the effect.

You can make adjustments to angles and such to try and fix things, which makes the CAD software invaluable.

Huh very interesting. Its cool that there is such highly specialized CAD software for this craft.

deleted by creator