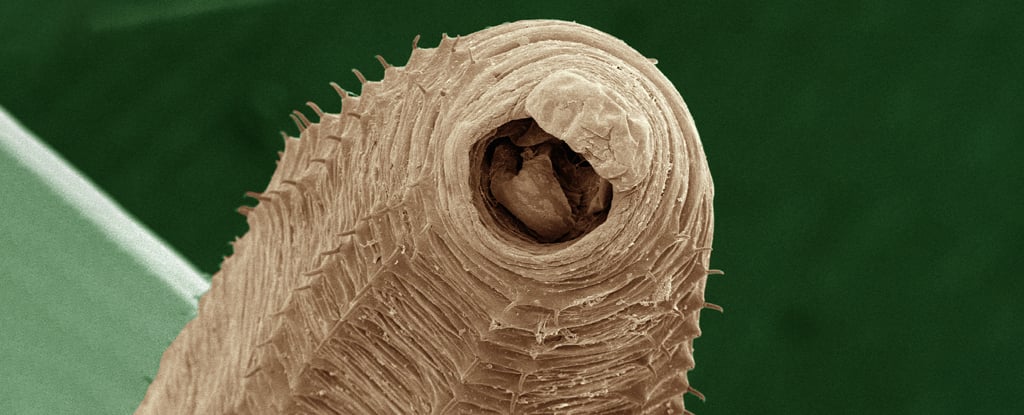

Back around when worms wriggled out of saltwater and into freshwater, they experienced a cataclysmic rearrangement of their genetic material.

This event ripped once functioning genes asunder, including some of those involved in critical cell division processes, leaving earthworms, leeches, and their other clitellate relatives with the most scrambled genomes known.

Three groups of researchers have now independently reached this same conclusion, upending a long held assumption that there’s a certain level of genetic stability required for animal species to avoid extinction.

Evolutionary biologist Carlos Vargas-Chávez, also from CSIC-UPF, and colleagues discovered gene loss is about 25 percent higher in the line of worms that became clitellata, compared to their other relatives.

They suspect the worm’s genomes scrambled in response to shifts into new habitats, but have yet to determine which came first, the worm’s ventures into freshwater and land or their genes’ adventures into new positions in their genetic molecules (chromosomes).