This post is not anti-wind farm. I just thought it shared some nice newly discovered information about a cool owl thanks to the availability of cheap mini GPS trackers. It also shows that the road to hurting our planet less is not a simple one. It poses as much danger of us not understanding or respecting our planet as much as previous means of energy production, and it is up to us to learn these details of how our planet works and finding ways of working within those boundaries.

From ABC News AU

Across Tasmania’s forests, a distinctive “boo-book” sound can sometimes be heard among the trees.

It is the call of common type of owl known as a Tasmanian boobook, or morepork.

“It echoes through the forest,” Associate Professor Rohan Clarke said.

Ahead of winter, some Tasmanian boobooks are known to migrate to the mainland, before returning home once the weather improves.

But until recently, their flight path across Bass Strait had never been officially recorded.

That was until Professor Clarke and a team from Monash University used GPS technology to track the owls’ journey between Victoria and Tasmania.

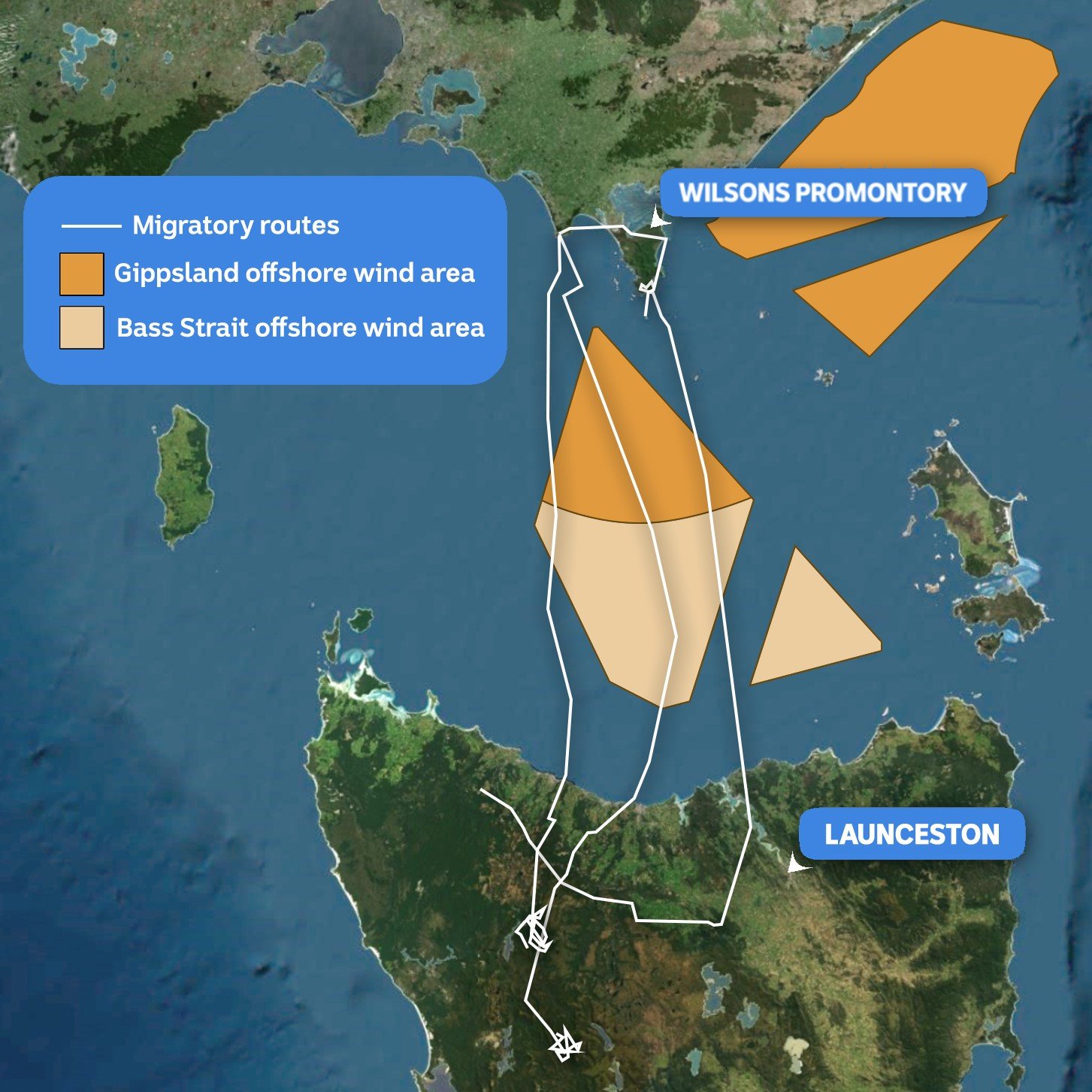

The results have highlighted a potential impending problem: the birds flew directly through two vast zones earmarked for large-scale offshore wind farms.

*A map of the migratory path of the owls. *

“That passage that takes them through the priority area for offshore wind development … just highlights that need to understand more … so that we can better quantify the risk,” Associate Professor Clarke said.

‘Green-green dilemma’

According to government-commissioned visualisations, the wind farms could have turbines with spinning blades that reach up to 270 metres above the sea surface.

Associate Professor Clarke said such infrastructure could pose a significant hazard to Tasmanian boobooks, as well as other migratory bird species crossing Bass Strait, including some that are endangered.

“One is a broad impact that sees birds change their flight pathways because of the existence of wind farms,” he said.

“And then at a finer scale, and a more direct level of impact for individuals, it’s collision risk with particularly the rotors — so, the spinning turbine — but also collision risk with the other infrastructure.”

Wind turbines in the sea.

Associate Professor Clarke described the situation as a “green-green dilemma”.

“We absolutely need to transition to renewable energy and clean energy sources,” he said.

"The greatest threat to biodiversity is undoubtedly climate change at a scale that is here and coming.

“So it’s not about preventing [wind farms], it’s about working out how we get to the right outcomes whilst minimising harm to biodiversity through that process as well.”

Lightweight GPS devices tracked boobooks

To track the owls, the Monash team headed to Cape Liptrap, a coastal headland in Victoria where the boobooks are known to begin their return journey back to Tasmania.

Using padded nets, the team managed to capture five birds.

They then stuck lightweight GPS- and satellite-enabled tracking tags on their tail feathers.

The team attaches a GPS tracking device to a Tasmanian boobook.

“Within about a month to six weeks, typically the tape fails and the tag naturally falls off, so the bird doesn’t have to carry it for too long as well,” Associate Professor Clarke said.

The team then waited for the owls to take flight, with the expectation they would “island hop” across Bass Strait, stopping off to rest on the Furneaux group of islands.

Instead, the tracking devices revealed the boobooks flew directly to Tasmania, covering the 250-kilometre trip without stopping.

“They just jump off the headland, and for want of a better term, they just boot south,” Associate Professor Clarke said.

Wilsons Promontory in Victoria, where some of the owls left mainland Australia.

Only three of the five tagged owls undertook the Bass Strait journey before their tracking devices ran out of power.

Of those three, one completed the overnight trip in about eight hours, while the other two did so in about 10 hours.

For comparison, the Spirit of Tasmania ferry takes between nine and 11 hours to travel between Geelong and Devonport.

The study has been published in the peer-reviewed journal Emu — Austral Ornithology.

More research needed for other migratory birds

There have been separate concerns that a wind farm proposal on Robbins Island threatens the orange-bellied parrot’s migration route. (Supplied: Dan Broun)

Bass Strait is one of three major “flyways” used by migrating birds in Australia.

The other two are Torres Strait and the Arafura Sea, in the country’s north, Associate Professor Clarke said.

Many species, potentially totalling millions of birds, travel along the routes each year as they come and go from breeding or wintering sites, he said.

“And yet we have almost no understanding of the details of that.”

Associate Professor Clarke said his team’s project was the first to track the flight paths of migratory birds across the length of Bass Strait using GPS and satellite-enabled technology.

Other research teams have also recently reported on the use of VHF radio wave technology to track critically endangered Orange Bellied Parrots across Tasmania and some Bass Strait islands.

Associate Professor Clarke said understanding the flight paths of all migratory birds, regardless of their threatened species status, was critical.

“These wind farms are going to be operational for 30-plus years,” he said.

“And if it turns out that they deliver unsustainable mortality events for even the most common species, then that can act as a really significant sink on [a] population.”

Any renewable energy infrastructure proposed for the offshore wind areas will need to undergo environmental assessments as part of the approvals process.