If you spend any amount of time on just about any prepper forum, you’ll see terms like “bugging in” or “bug-out bag”. There is a TON of bad information out there, so I wanted to take a second and make a no-nonsense, plain-language primer for anyone just getting started on their preparedness journey.

Put simply, when people talk about “bugging out”, they mean rapidly evacuating an area (usually their home) in an emergency. This can be due to things like natural disasters, chemical spills, civil unrest, war, or getting a call about a sick family member at 3 AM. Bugging out can be, but doesn’t have to be, permanent.

You’ll also see some people talk about “bugging in”. This means that instead of evacuating, they stay at home in an emergency. There’s merit to this approach as well: you already know your home and community, and all your supplies are (hopefully!) already there. This is especially appropriate in emergencies that are either very short in duration (like a two-day power outage) or very extreme in scope (like natural disaster making major roads out of your area impassible).

Whether it’s better to bug out or bug in depends on your needs and circumstances; there is no “best” answer that applies equally to everyone in every situation. But there are a few things you can do in advance to help you decide:

- Think about the emergencies that are likely to occur in your area. Severe weather? Spill at the nearby chemical plant? Start an emergency manual by listing these emergencies and how you’d react. Document any special circumstances that might change your normal plan.

- In your emergency manual, decide on a bugout threshold for each emergency. Maybe “widespread flooding” isn’t worthy of evacuation because your home is on a hill, but “Somename River exceeds 35 feet” cuts off the main route in and out of your home.

- Also in your manual, decide under what circumstances you’ll bug in. For example, it may be safer to stay home during a tornado outbreak.

- Pick one or more bugout locations in advance. Wherever you go should be far enough away that it’s unaffected by whatever you’re evacuating from. If you plan on bugging out to a friend’s or family member’s home, make sure they know about your plans in advance! Just showing up unannounced is a great way to be turned away.

When the time comes and you decide to bug out, review your plans in light of whatever the actual circumstances are at that time. Is your destination still unaffected? Can you get there safely? Is your family (including pets!) able to travel safely? Just because you planned to bug out (or bug in) doesn’t necessarily mean you have to do so. Always stay flexible. Unyielding adherence to plans is a fast path to failure.

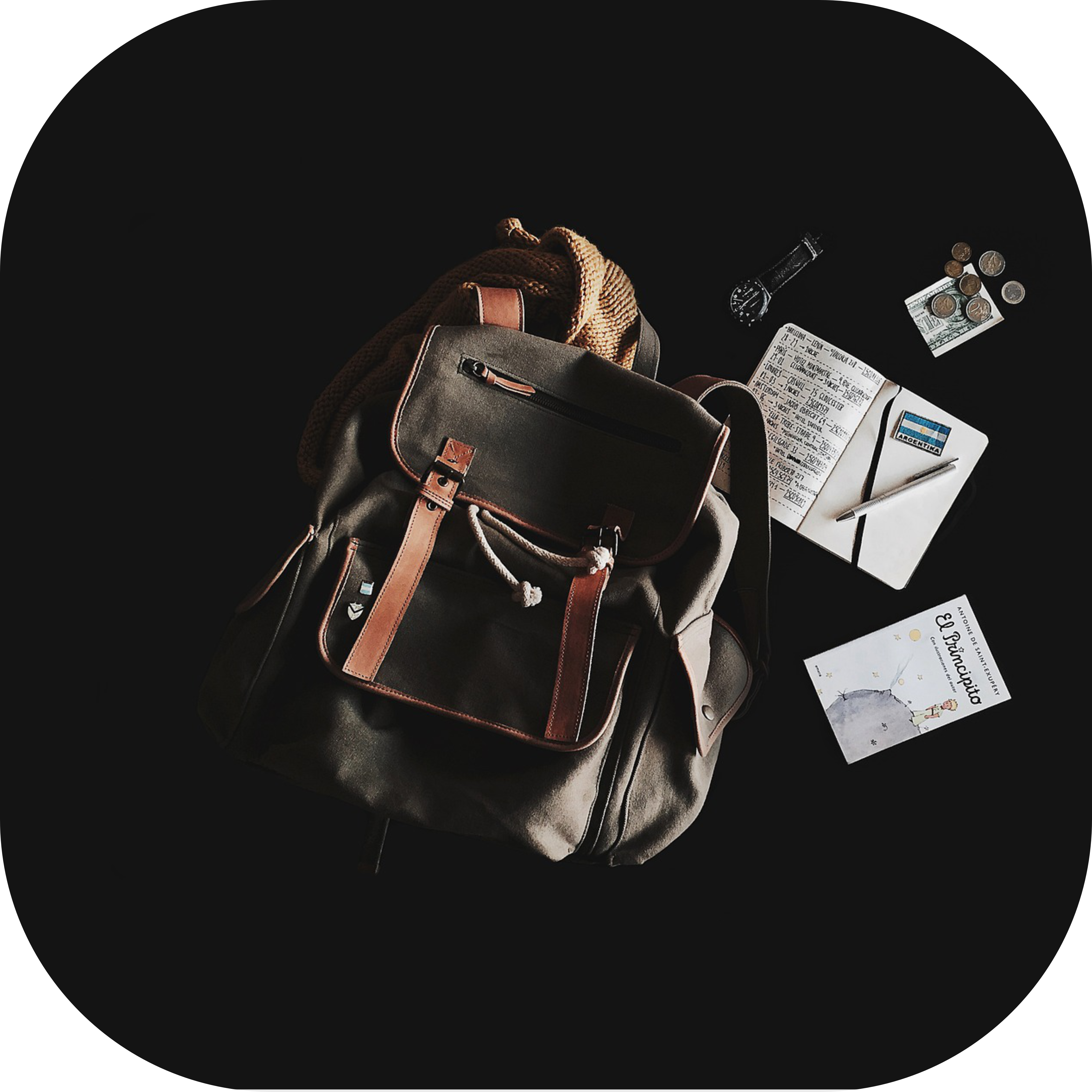

Finally, you’ll see a lot of people talking about a bugout bag (“BOB”). This is basically a pre-packed backpack or duffle bag that you can grab on your way out the door. There are lots of good guides on building one, and I can make another post going into more details later (feel free to beat me to it). But a basic checklist includes:

- A seasonally-appropriate change of clothes. At a bare minimum, one or two pairs of socks & underwear.

- Any medication you may need. If you have prescriptions, talk to your doctor. “Hey doc, I’d like to keep a small supply of my prescription on hand in case I have to travel in an emergency and forget to pack. How can I do this?”

- A basic first aid kit. Building one yourself is usually cheaper and gets you better quality gear, but you can also buy a small ready-made kit just about anywhere.

- A multi-port USB charger, a small travel surge protector, and enough cables to charge your gear.

- Two compact flashlights with spare batteries. If you’re using alkalines, keep the batteries in a separate container to reduce the odds of leaks.

- A paper map of your region. You can get these for free through most states’ visitor centers.

- A basic toiletry kit. In my case: bar soap, soap sock, travel size toothpaste / shaving cream / deodorant / mouthwash, cartridge razor. I normally use a safety razor with blades, but if you have to take your bugout bag through TSA, you may get a hard time about the razor blades.

- Poncho, emergency blanket.

- A printout containing emergency contacts (family members, employer, bank / credit card issuers, insurance carriers, etc). Policy numbers are fine but don’t put account numbers on there; your bank / card issuer can look you up by your social security number.

- A notepad with several pens

- A few paperback books

- Enough cash to fill up your gas tank three times. Keep it to small bills ($20 and under).

Feel free to add your own items below. I’m sure I missed some but this will be enough to get you started with a functional, balanced bag. I see a lot of people in various prepper forums building up their BOB like they’re going to ride out WW3. That’s not what a BOB is for; a BOB is to get you from point A to point B. And don’t feel like you have to buy some special “tactical prepper backpack”; that old Jansport tucked in the back of your closet is fine, and secondhand laptop backpacks can give you tons of organization for very little money.

To give a real-world example, I live near a nuclear plant. Whatever your thoughts on nuclear power, there’s a nonzero chance that I may need to evacuate someday. So here’s a slightly redacted example from my emergency binder:

In case of an emergency at the nuclear plant, local sirens will sound a steady tone for 3-5 minutes. Phone alerts may or may not go off. All local radio and TV stations should break in with news, but the following are part of the actual emergency plan:

- TV station #1

- Local radio station #1

- A few other radio stations serving the major metro areas within 100 miles

SPECIAL NOTE: If grid power has been down for at least ten days AND a plant emergency occurs, proceed to evacuation. The plant has at least two weeks of diesel on site for their backup generators but if this can not be replenished (severe weather, severe civil unrest, sabotage, etc), the plant’s safety systems will lose power. Catastrophic events will follow.

Follow instructions provided by civil authorities. Begin calmly and discreetly preparing for evacuation:

- Evaluate situation. If appropriate, invite (elderly relatives) to our place to prepare for evacuation. 1a) If inviting (elderly relatives), advise them to bring their bug-out bags. 1b) If weather is inclement, we may need to go pick them up. Do not leave the house unattended; only one adult should leave the home.

- Discuss with kids. Keep them calm. Offer to allow them to participate with step #s 4-7 and #9.

- Fill both vehicles’ gas tanks, one at a time. Park both vehicles in garage upon return.

- Fill water bottles with filtered potable water.

- Close blinds in library (our library is a small room off our foyer). Use this as staging location for supplies.

- Pull both pet carriers and pet bug-out bag. Stage in library.

- Pull all four bug-out bags. Stage in library.

- Continually monitor news for updates. Bias towards evacuation; it’s easier to come home after an unnecessary evacuation than to evacuate once the roads are gridlocked.

- Calmly and discreetly load change of clothes, laundry detergent, (my + kids’) bugout bags, and four freeze-dried food tubs in the SUV. Load (wife’s + pets’) bugout bags, one freeze-dried food tub in sedan. Load pets in SUV or sedan based on whether we’re hauling (elderly relatives)

- If the situation deteriorates or authorities advise, evacuate using the routes listed below. In all cases, evacuate at least 100 miles to the north or west.

Preferred evacuation route: Take I-1234 north 45 miles to I-5678 west. Take I-5678 west 15 miles to US-2345 north. Take US-2345 north for 70 miles to the town of Sometown.

Alternate evacuation route: (similar instructions in another direction)

Hi,

much appreciated post!

Some thoughts:

- If you really need to formalize and write down every plan in a binder should be open to discussion.

- Threats and threat level differ from land to land and region to region. Prepping in the states is totally different from being prepared in the EU and elsewhere.

- Like you said: not all risks are equally probable. The ideas of risk management (likelihood, harm, cost of avoidance, cost of arrival) could be applied to identify your personal risks.

- A good addendum would be the mode of transportation. Not everyone has a car…

In my opinion preemptively leaving your place when e.g. trains are still going would be preferred over strolling the wild in a big evacuation movement.

Best wishes

Good points all around. The EU thing specifically is big. Our geography here in the US means just about everyone has somewhere to evacuate to without too much hassle, at least in terms of location. Whether they’d have a place to stay there is another matter.

For the binder, my thought is that it’s good to think about these things ahead of time. When we’re in the heat of the moment, dealing with the stress of whatever is going on, we may not always be thinking clearly. Taking the time to think about your plans today when things are calm gives you a running start tomorrow when they aren’t.

That said, remember the old saying: “no good plan survives first contact with the enemy”. The binder should be thought of as a guideline rather than a rigid set of instructions. Always make adjustments based on your own individual situations and risk tolerance.

EU also means, that the distances are shorter: help might be much nearer, in case of rather local events. Also the population density is in parts higher, which could be troublesome in some scenarios…

The other aspect is that in the US delivery routes are much more fragil and the impact on isolated locations bigger. I mean it makes sense to hoard tons of food if the infrastructure is known to be shaky.

In regards to assessment: I hear you. Some risks can be mitigated, some are too expensive to mitigated. You need to assess and reassess your individual situation and risks in a manner that does not drive you nuts and is rooted in reality.

I find it much more helpful to prepare resourcefulness rather than plans. Meaning: I invested in outdoor hobbies to make sure to know my gear and ways around. If I had to evacuate by train, bike or feet, I am sure I would have the capabilities to get to my desired (pre-planned) location.