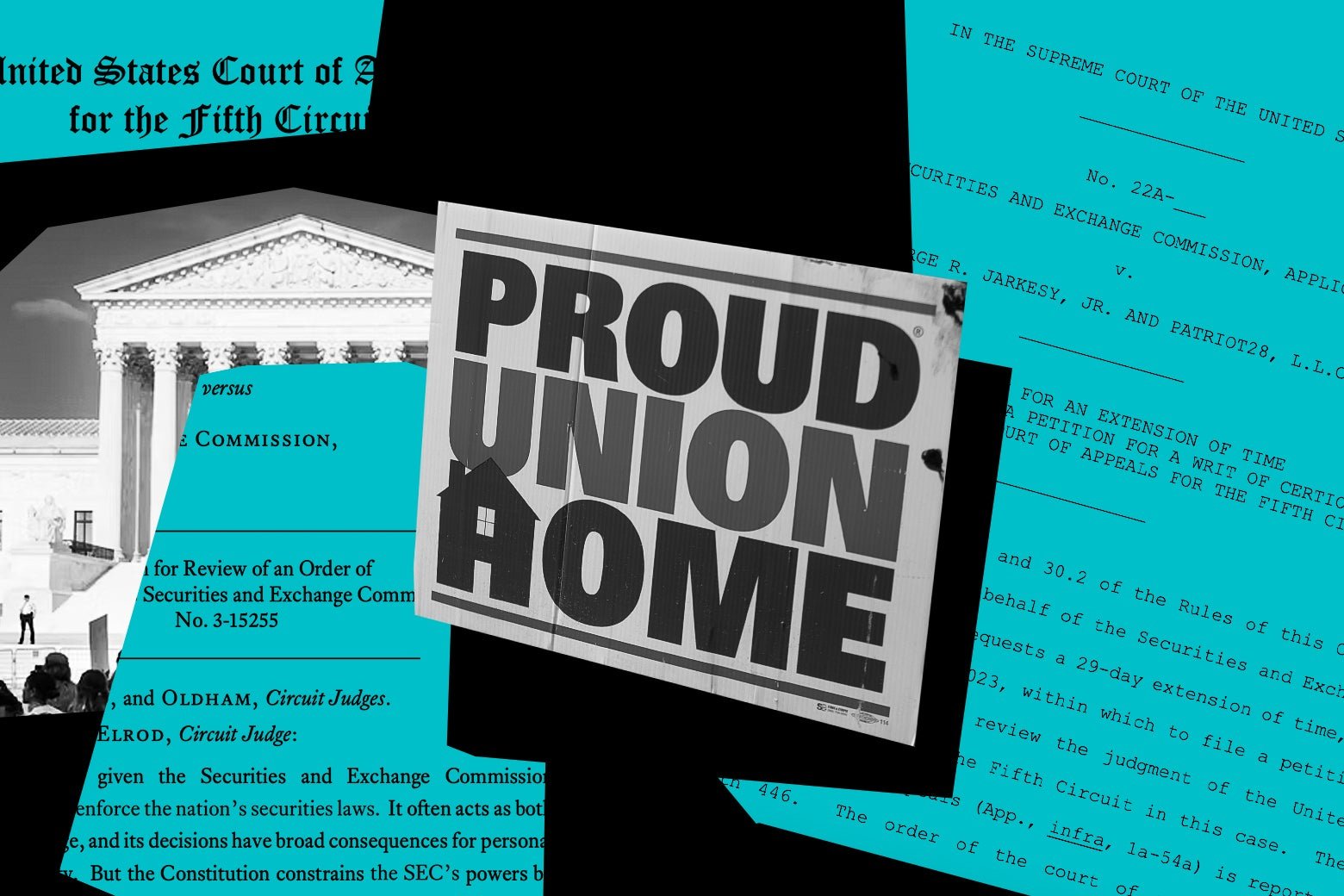

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jarkesy to review a ruling that set aside a decision of the SEC that the hedge fund manager George Jarkesy committed fraud when he misrepresented his financial position to investors. Based on that finding, the agency barred Jarkesy and his company from certain parts of the investment business, imposed $300,000 in penalties on him, and required him to disgorge unlawful profits of nearly $685,000. What makes this case so extraordinary is not that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit concluded that the SEC’s decision was unconstitutional, but the substance of the three separate grounds it found for doing so. If the lower court ruling is upheld, it would likely make adjudications by most federal agencies (and not just the SEC) a thing of the past. Here’s why.

The legal arguments are complicated, but the consequences of the 5th Circuit’s ruling, if upheld, would be straightforwardly devastating. First, Jarkesy argues that the SEC’s decision must be vacated because the agency sought civil penalties and disgorgement of unlawful gains in an agency proceeding and not in a federal court, where he would be entitled to a jury trial under the Seventh Amendment. The result would be the demise of agency proceedings if any agency―not just the SEC―sought monetary relief except in federal court. Not all agencies have the statutory authority to bring cases in federal court, and if they wanted the right to recover money from a wrongdoer, today’s stalemated Congress would need to act (it won’t). Even agencies that currently have the right to go to court would have to choose between getting full relief in court or settling for an order stopping the unlawful conduct, which they could do in an administrative proceeding. And to the extent that agencies choose the federal court route, those courts would see a significant increase in complex litigation, with no new judges or additional resources.

This is all part of the plan.

If they can’t get the laws invalidated, they’ll just make the laws impossible to enforce.

Don’t like gun control legislation? Well here’s a Supreme Court ruling saying that gun legislation has to be rooted in 18th century law for the legislation to be valid.

Witness intimidation? Jury Tampering? Sorry, those are trumped by the attacker’s first amendment rights to free speech.

Voting rights laws? Sorry, only the DOJ can bring those cases up at all. The people actually doing the voting have no legal standing.

Federal agencies trying to rein in illegal corporate behavior? Yeah, no. Not unless Congress specifically authorizes you to for each and every case. And even then, only under the most convoluted circumstances.

This is the whole point. They tried going the “Ban it all, and everything even remotely related to it too.”, and it blew up in their face. So now, in order to avoid political backlash, they keep the laws on the books and just quietly make them impossible to enforce in order to have the same practical effect.

And I know I sound like a bit of a conspiracy theorist here, but this leads to a path where things like this suddenly become a very distinct possibility:

“As the founding fathers did not specifically include communication via devices such as the telephone or internet, no laws protecting a person’s freedom of speech applies to electronic communications. We hereby rule that the government has the absolute authority to regulate speech via electronic communications as they see fit. If the founding fathers wanted speech via electronic communications to be protected, they would have included that in their writing of the First Amendment. Since it was not specifically included, it’s clear that the Founding Fathers had no intention of allowing freedom of speech to extend to electronic communication.”

And if you think that’s hyperbole, remember that it’s the exact logic they used in their ruling about the 2nd amendment.

deleted by creator

I would assume they’re talking about the old federal assault weapons ban ruling?

deleted by creator