It came at the cost of having no tail!

I’ve always wanted a prehensile tail. Maybe CRISPR can make that happen someday 😜

On a more serious note, it really bothers me when evolutionary biology articles say “this must have some advantage”, because that’s simply not how evolution works.

A trait can be absolute dogshit and still get passed around even with no advantage. It just depends how big the population is in the first place and how deadly the trait is. If it’s mostly benign, and the founding population isn’t huge, it’s going to persist regardless of usefulness. Especially if it’s a dominant expression.

Really a trait can be extremely deadly, as long as it doesn’t kill you before you procreate.

Just look at Koalas.

With my luck, mine would probably be a just as attractive and just as useful as a pinky toe

This is the best summary I could come up with:

A single genetic tweak that occurred among our ancestors 25 million years ago means humans today are unable to grow a tail, according to a new study.

Humans’ ancestors started off with a tail, but about 25 million years ago, they dropped the appendage, leaving it to other tree-dwelling primates like monkeys.

It’s still not clear exactly how the mutation leads us to be tail-less, Miriam Konkel and Emily Casanova, two experts who commented on the work but were not involved in the study, said in an opinion piece in Nature.

Scientists found that adding the Alu sequences to the TBXT gene in mice didn’t only truncate their tails, it also gave them an unusually high level of a defect in the neural tube, a structure which later turns into the nerves in the spine and the brain.

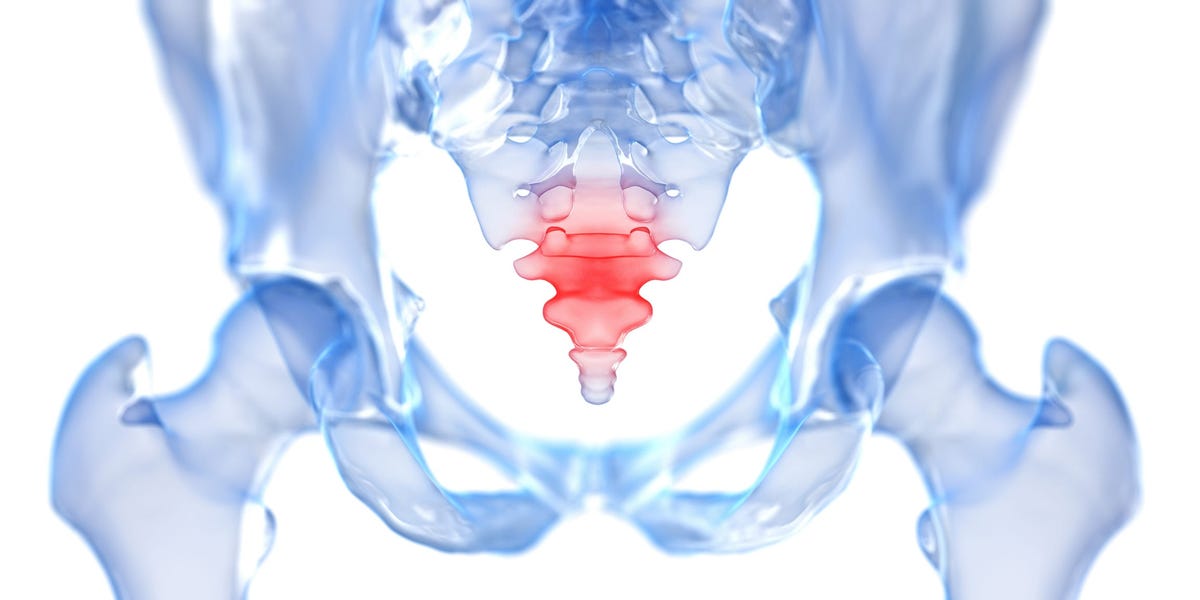

In humans, that defect is known for producing spina bifida, which is when the baby’s spinal cord doesn’t completely close, leaving a bit of the spine and some nerves exposed on the back.

“We apparently paid a cost for the loss of the tail, and we still feel the echoes,” Itai Yanai, a study author and graduate researcher at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, previously told Science magazine.

The original article contains 773 words, the summary contains 206 words. Saved 73%. I’m a bot and I’m open source!