Great article, I forgot that he was on the Lions with Wayne Fontes during the Barry Sanders era!

Anyone able to paste the article in a comment to get around the paywall?

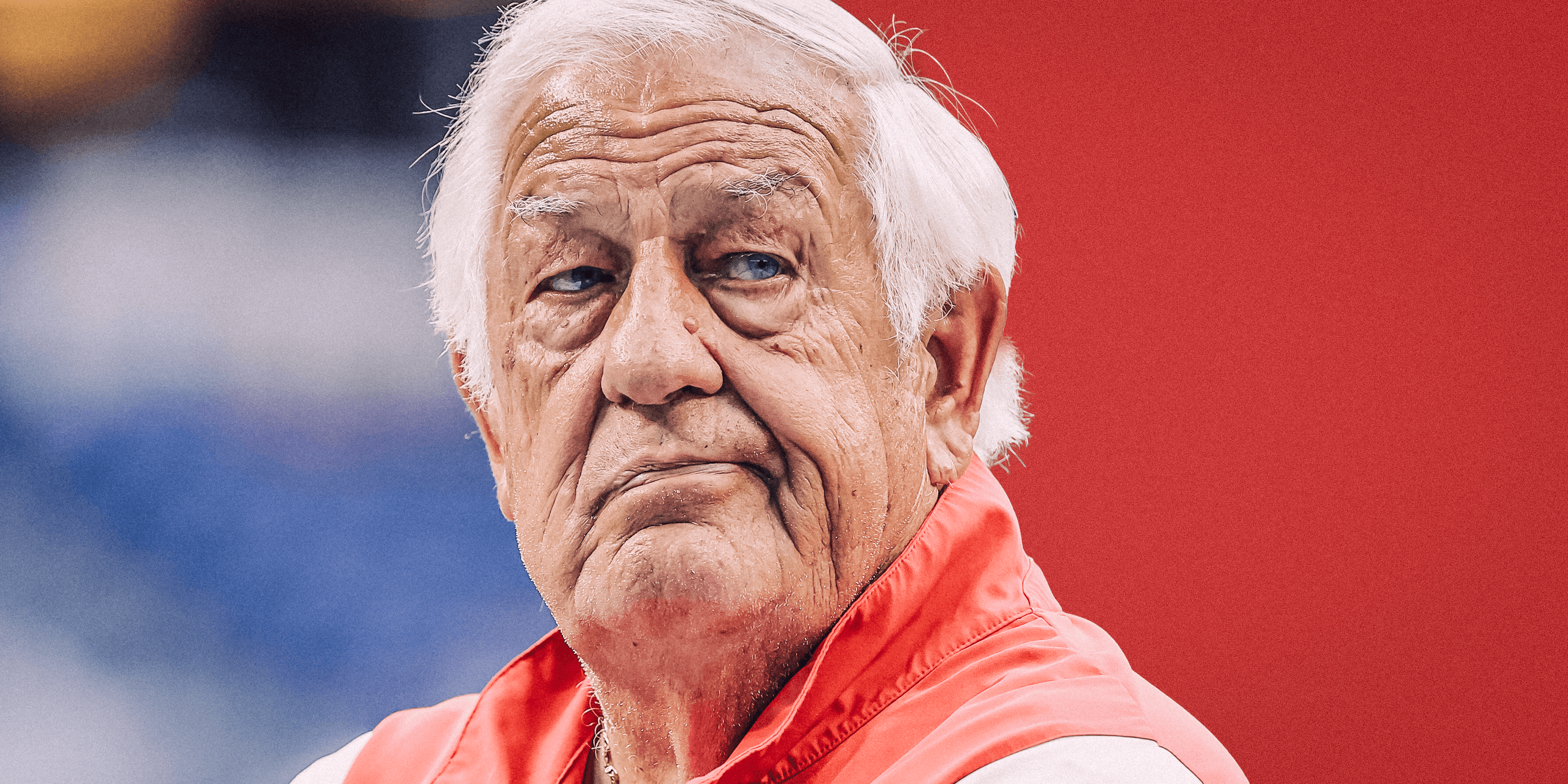

TAMPA, Fla. — Every morning starts the same: a drive through the pre-dawn darkness, a 3:15 a.m. arrival and pages of play calls he likes to sketch in pencil. That’s how Chuck Noll taught him, and that’s how Tom Moore’s done it ever since.

Sleep in? The man’s offended. “Lay there and stare at the ceiling?” he groans. “I’m 84. I’m not sure how many days I’ve got left to live, but I know one thing: I ain’t gonna waste them sleeping.”

He’s been at this almost 70 years. His stops include Korea, where in the 1960s he led a team in the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Division, and the long-defunct World Football League. Back then, the New York Stars played their home games at Triborough Stadium, where the lights were so shoddy they couldn’t televise the games. But, Moore points out, “if you had a choice room at Rikers Island jail across the river, you could see the field just fine.” He didn’t get paid the last six months of the season and left dead broke.

GO DEEPER

‘The biggest disaster in professional sports history’: Remembering the World Football League

By 1977 he’d found his way to the NFL, working under Noll in Pittsburgh. Moore spent the next five decades scripting a career as one of the greatest offensive minds in league history — and perhaps the most overlooked. “Before you had play callers getting all this attention, Tom was doing it better than anyone else,” says Clyde Christensen, who coached in the NFL for 26 years. “We’re talking about one of the best play callers of all time.”

During Moore’s 45-year NFL career, he worked with Lynn Swann and John Stallworth in Pittsburgh, Cris Carter in Minnesota, Barry Sanders in Detroit, Peyton Manning in Indianapolis, Larry Fitzgerald in Arizona and Tom Brady in Tampa Bay. And he did it by signing 45 contracts without ever hiring an agent. “If I can’t get a job myself, I don’t deserve it,” he says. “And I don’t want it.”

In June, Moore was honored with the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s Award of Excellence; by July, he was back on a practice field, barking one-liners at players 60 years his junior. His current title: senior offensive consultant for the Buccaneers. More to the point: He’s a coaching lifer who can’t quit the game.

“What am I gonna do?” Moore says. “Hang out with old people?”

And ask anyone who’s ever suited up for him: this man’s words stay with you.

‘It’s a simple game. We make it hard.’

Before a road game at New England during Manning’s second season, Moore, the Colts’ offensive coordinator, was worried the Patriots would sniff out a play that burned them a year prior, a slant-and-go to Marvin Harrison that went for a touchdown. He warned Manning about using the same play call.

“Just call it and I’ll change it to a slant-go-slant,” the QB replied.

“Come up with a new name for it,” Moore urged.

Manning repped the new route with Harrison all week, and on the second drive of the game, the Colts advanced to the Patriots’ 10-yard-line. Moore wanted the slant-go-slant but realized he didn’t know the verbiage. So he improvised.

This is what Manning heard in his helmet:

All right, Peyton, let’s run dice run … scat right … ummm …

… you know what, Peyton?

… just run whatever the f— you and Marvin have been working on.

The Colts’ equipment staff — standing right next to Moore on the sideline — erupted with laughter.

“I assume a lot of people have this idea that in the NFL, we’ve got this sophisticated language and all these complex play calls,” Manning says now, trying to hold back laughter. “Well, sometimes it was as simple as Tom yelling at me to run whatever the f— Marvin and I had been working on.”

The slant-go-slant went for another touchdown.

‘Players, not plays.’

Moore was a young wide receivers coach in Pittsburgh when Swann walked into his office one morning and shut the door.

“John and I are good receivers,” Swann said of him and Stallworth. “We know how to catch, we’re gonna play a long time and make a lot of money. We need you to teach us what we don’t know.”

“Well, what don’t you know?” Moore asked.

“How to recognize and beat coverages.”

Moore drilled the pair on different defensive schemes, then showed them the routes that would beat each. The secrets came in the subtleties, Moore stressed, like how a cornerback’s feet were lined up before the snap. For the two receivers, the best years of their Hall of Fame careers would follow. So would two more Super Bowl wins.

Moore spent his first 13 NFL seasons coaching under Chuck Noll in Pittsburgh. (George Gojkovich / Getty Images)

As offensive coordinator in Detroit in the mid-90s, Moore designed his scheme around Sanders’ inimitable talents. “He wouldn’t say anything to anybody,” the coach says of the Hall of Famer. But man, he worked. Moore used to marvel at how every day after practice, Sanders would stay on the field to run gassers alone.

“Coach, I watch a lot of film, but what I see on that screen and what I see on the field aren’t the same thing,” Sanders once told him. “Every game starts out really fast, but the more carries I get, the more it all slows down.”

Sanders wanted 25, 30 touches a game. Moore obliged. “There was no running back by committee with Barry Sanders,” he says. “He’d have 12 carries for 38 yards. Then he’d have 18 for 185.”

In Indianapolis, he and Manning shared a maniacal drive — Moore arrived before the crack of dawn to sketch out new plays, while the QB stayed late to pore through film, sometimes falling asleep with the remote in hand.

“Thirteen years with the Colts and I can’t think of one meeting Tom wasn’t in there with me,” Manning says.

Moore skipped his own brother’s funeral so he wouldn’t miss a practice. Until his neck injury in 2011, Manning didn’t miss many, either. Once, while ESPN’s Jon Gruden and Ron Jaworski were watching practice before a “Monday Night Football” game, Gruden asked Moore why Manning’s backups never got a single rep.

“Fellas, if 18 goes down, we’re f—ed,” Moore told them. “And we don’t practice f—ed.”

Gruden told Manning about the comment later.

“You can probably debate it in different ways,” Manning says now. “When I got injured in 2011, it sort of showed itself (the Colts went 2-14), but that’s just how we practiced in Indy. We had guys who just didn’t come out — ever. That was how Marvin practiced. I remember when Reggie (Wayne) got there, he was like, ‘Oh, this is how it is?’ So he never came out, either. And if they were in there, I was gonna be in there.”

‘It’s 1-2-3, throw the m—–f—er away. If you don’t, they’re gonna be carrying you out of the stadium boots first.’

As a coach, Moore was rigid and unrelenting, especially with young quarterbacks. This is the line they’d hear if they held onto the ball too long.

“Jim Sorgi probably still hears that in his sleep,” longtime Colts tight end Dallas Clark says. “And then wakes up in a cold sweat.”

For the rookie offensive lineman who jumped too soon: “Son, I hope you come from a rich family, because it’d be a shame you don’t make this team because you can’t stay onside.”

Before the team would break for summer: “Don’t go showing your high school or college coaches our playbook. This is our playbook. These are my plays. Tell your coaches to wake up a little earlier in the morning and come up with their own goddamn plays.”

Eventually, Manning and a few teammates printed off T-shirts with all of Moore’s one-liners.

“He handed those T-shirts out like they were his business cards,” Manning says.

‘We don’t got any Northwesterns on this schedule.’

This was a nod to Moore’s days as Iowa’s starting quarterback, when the Wildcats were a Big Ten bottom-feeder. After the Army, the WFL and five stops in college football, Moore landed a job at the University of Minnesota. That’s where, in the early 1970s, he recruited a talented but temperamental quarterback out of Jackson, Mich.

[ Table of his coaching career]

“Believe it or not, I had a temper back then,” Tony Dungy admits. “I was a yeller and a screamer and a terrible loser, a total hothead.”

Initially, Dungy didn’t even want to visit the campus; he’d never even been on a plane before. It was Moore who finally convinced him. And after Dungy won the starting job, it was Moore who taught him how to keep his emotions in check.

“If you’re gonna be the quarterback for this team, then you’ve gotta be under control,” Moore scolded.

Dungy was the team’s MVP his last two seasons but went undrafted in 1977. He then signed with the Steelers as a defensive back after the team’s new wide receivers coach convinced Noll to give him a shot.

“Without Tom in my life, who knows what would have happened?” Dungy says now.

Twenty-five years later, Dungy landed in Indianapolis as the Colts’ new head coach. Moore was already in place, and Dungy never once considered making a change.

“Now, instead of him telling me what to do, I was his boss,” Dungy says. “It didn’t even seem right.”

‘Pressure is what you feel when you don’t know what you’re doing.’

It was Week 14 of the 2000 season. The Colts were in an early 14-0 hole to the Jets, and Moore was incensed. “Peyton,” he barked at Manning on the sideline, “we’re going no-huddle the rest of the game.” The QB nodded, and while their second-half rally came up short, a thought lingered in Moore’s mind during the flight home.

“Why are we waiting to get down 14?” he asked Manning.

Manning wanted to start in the no-huddle and wanted total control at the line of scrimmage. He felt he’d earned it. So that evening, Moore decided the Colts were going to speed up — a decision that would reshape NFL offenses for years to come. They’d start every game in the no-huddle, called Lightning. Manning would have complete command, perhaps more than any other quarterback in league history.

“Defenses want to substitute every three plays, but they ain’t doing that against us,” Moore says. “Their ass is gonna stay on the field.”

It was an audacious gamble, handing over that level of responsibility to a third-year QB who’d thrown a league-record 28 picks as a rookie. Previously, Moore would dial up three plays — a run to the right, a run to the left and a pass — and Manning would decide on one, depending on the defensive front he saw. In Lightning, it was one play with options Manning could check into. Or, he could scrap it altogether and call a new one. The QB would run the show.

“Tom basically said, ‘We’ve got this really smart quarterback, and we’re going to let him use his brain as a weapon,'” says Christensen, then the Colts’ wide receivers coach. “Honestly, not a lot of coaches back then were secure enough to do something like that, just turn their system over to one player.

“But it gave Peyton so much confidence. It’s not like Tom was giving the keys to Jim Sorgi or Curtis Painter.”

Most of the time, when Moore would begin rattling off the call, Manning would pound his chest, their signal that he knew the rest. Moore would wave back from the sideline. You got it, kid.

“Not every QB wants that type of responsibility,” Dungy says. “But we had one who did.”

Peyton Manning won four MVP awards partnering with Moore in Indianapolis. (Al Messerschmidt / Getty Images)

The Colts finished in the top three in scoring five straight seasons. Manning started piling up MVP awards. Before every game during that stretch, Moore would leave his QB with a few words before he jogged onto the field: Play smart, not scared.

That’s how Moore coached and how he called plays: without fear. The success that followed? That was the players, Moore insisted. Any failures were on him.

“I always used to tell Peyton this: You throw the touchdowns, I call the interceptions,” Moore says. “If you think you should do something, do it, and if they don’t like it, they can come see me. You can do no wrong. Don’t call plays and checks at the line of scrimmage wondering if it’s the right play. That’ll drive you crazy.

“You know what you’re doing. Do your thing and don’t ever, ever look back. If you make the wrong decision, you didn’t — I didn’t do a good enough job coaching you. I’ll take the hit.”

Manning remembers that speech, almost verbatim, two decades later. “I never took that for granted,” he says.

‘Two men in a phone booth. One comes out.’

During film sessions in Indy, Moore would show his players cut-ups of opponents slacking late in games, singling out their best players to drive the point home. This thinking would plant the seeds for some of the most memorable comebacks in league history.

“Including one right over my shoulder,” Moore says from his office in Tampa, a nod to the 21-point deficit the Colts erased in four minutes against the Bucs in 2003.

As Manning pointed out, the Colts’ skill position players were in tremendous shape, rarely taking a rep off in practice. Add in Moore’s intolerance for mistakes and the unit grew into a finely tuned machine, especially late in games.

“We’re talking 70,000, 80,000 fans on the road screaming bloody murder,” Clark says, “and we were as cool as the other side of the pillow.”

His mind goes back to one night in New England, the Colts clinging to a slim second-half lead, not wanting to give Brady a chance to rally. Deep down, Moore knew the Patriots had no answer for Edgerrin James, so he dialed up the same run play, “Belly,” a dozen times in row.

“Literally, 12 times straight,” Clark says. “We ran Belly right up their ass.”

James kept moving the chains. Not even Bill Belichick could figure a way to stop him. The Colts won going away.

“I promise you,” Clark says, “Tom Moore goes to bed thinking about that drive at least once a month.”

‘Take the mystery out of it, brother.’

Moore was always going to coach as long as he could. While he was a graduate assistant at Iowa in the 1960s he tried a semester of law school but hated it. His backup plan if it didn’t work out? The FBI.

“But then I got a job at the University of Dayton, and that was that.”

After his run in Indianapolis ended in 2010, Moore spent seasons as a consultant with the Jets (2011) and Titans (2012). Later that winter, an old friend called him up, asking him to come with him to Arizona, where he’d been hired as the new head coach.

“I’m getting the gang back together,” Bruce Arians told him.

“I’m in,” Moore replied. “Hell, it’s better than cleaning up dog sh–.”

In the desert, Moore helped Fitzgerald, then a decade into his career, find a different gear. The wideout can still remember the old coach barking at him during practices, refusing to let him ease up.

This is what Marvin Harrison would do … This is what Reggie Wayne would do … When I was in Pittsburgh, and we told John Stallworth to block Jack f—ing Tatum, he would put his face in Jack Tatum’s ear …

“I loved being coached hard like that,” Fitzgerald says now.

The 11-time Pro Bowler credits Moore with the single greatest quote he ever heard on a practice field. One afternoon, the Cardinals were sloppy, and the curmudgeonly old coach had seen enough.

“Men, the grass is greenest right next to the septic tank,” Moore told them.

“Everybody always thinks, ‘Oh, if I sign here, if I go work with this quarterback, everything works out,'” Fitzgerald explains. “What Coach Moore was saying was you gotta go through some hard sh–, some hard times, some really, muddy, nasty situations, in order to define who you want to be in this league.

“The funniest thing about it: I was like 31 when he said it, but everyone else on that team was in their early 20s. I was like, these m—–f—ers don’t know what a septic tank is!”

‘Sundays at 1 p.m.? Now that’s powerful.’

It’s pushing 100 degrees in Tampa and training camp’s not yet a week old. Moore lumbers around the Bucs’ practice field with a frown on his face, chirping at players too young to know where he started.

When one of those players, left tackle Tristan Wirfs, hears that Moore coached Lynn Swann back in the day, he shakes his head.

“Oh my God, really?”

Wirfs remembers watching Moore work with Brady, thinking to himself, “Tom Brady’s literally seen everything in this league, but if there’s one guy who’s seen even more, it’s that guy.”

In Korea, Moore led a team from the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Division in a game called the Sukiyaki Bowl. (Courtesy of Tom Moore)

Moore got the job with the Bucs when Arians became the team’s coach in 2019. When Arians stepped down in 2022, Todd Bowles kept Moore on.

“He tells the truth, and believe it or not, young players like it when you tell them the truth,” Arians says. “One thing Tom ain’t gonna do is bullsh– you.”

His mind, especially when it comes to offensive football, remains as sharp as ever. This past summer, former Jets QB and current FOX analyst Mark Sanchez flew to Moore’s offseason home in Hilton Head, S.C., for four days of film study. He needed Moore to help him better articulate the game.

For a while, it used to bug Moore that he never landed a head-coaching job. He interviewed once, with the Lions in 2006, but the gig went to Rod Marinelli. More than anything, he’s grateful. For the players he’s worked with. The coaches. The executives. For the moments that have stayed with him, like the four Super Bowl wins he’s been a part of and the rush he still gets before kickoff.

“Sunday at 1 p.m.? Now that’s powerful,” Moore says.

He ruled out retirement a long time ago. Sitting around? Relaxing? To him, that sounds miserable. Tom Moore was born to coach. He’ll do it until he can’t.

“I’m never quitting,” he says. “I’m doing this until they carry my ass out boots first.”

***Left out the table bc it didn’t format correctly on mobile